The Prosecution of Roger Ver: A Lawfare Case Study

by Taylor Hudak

“This lawfare isn’t really about taxes. It’s about control. Ver has long challenged both permanent Washington and centralized finance…. They see him as a threat.”

~ Tucker Carlson

Crypto pioneer and entrepreneur Roger Ver is well known as one of the first crypto investors in the world. As an early advocate of Bitcoin, Ver obtained the moniker “Bitcoin Jesus” for his promotion of and enthusiasm for what was, in 2011, a new technology.

Beginning at a young age, Ver developed a deep interest in economics and understood early on the importance of freedom of transaction and decentralization. For him, personal sovereignty, non-interventionism, and limited government were essential for America’s success. Thus, at only 21 years old, eager to share these ideas with others and initiate positive change, Ver ambitiously entered the political scene in the state of California as a libertarian. He used the opportunity to raise awareness of the corruption of law enforcement and the intelligence agencies while advocating for an end to mass killing and war.

Like many others who expose government wrongdoing, Ver faced serious retaliation from selective prosecution to repeated Internal Revenue Service (IRS) audits. Left with no other option, Ver made the difficult decision to expatriate from the United States in 2014. Despite this, Ver, who has a natural entrepreneurial drive, persevered and grew his businesses into successful international companies. Meanwhile, he continued to strongly advocate for Bitcoin and decentralized systems while assisting various humanitarian causes around the world. By 2024, things were looking up for Roger Ver until his life took a shocking and dramatic turn. [Note: Interested readers can skip to the detailed Case Timeline here.]

“Are you Roger Ver? Are you Roger Ver?”

It was a moment that will likely stick with Ver for the rest of his life. While attending a crypto conference in Barcelona, Spain, a man in the lobby of Ver’s hotel approached him and asked several times, with a thick Spanish accent, “Are you Roger Ver?” A puzzled Ver responded affirmatively, whereupon the man pulled out a badge and an Interpol arrest warrant and arrested Ver at the request of the U.S. government. Completely blindsided and in shock, Ver immediately felt as if the bottom of his stomach had dropped out.

Later that day, when Ver failed to show up for a planned dinner and failed to attend an interview, his friends suspected something was very wrong. “He never showed up [to the interview], which was totally out of character for him, and I got concerned pretty quickly,” said Steve Patterson. “When I learned he was arrested in Spain, I felt sick.”

Following his arrest, Ver was imprisoned for three and a half weeks at the Can Brians Penitentiary, the same prison where John McAfee allegedly committed suicide. After being released on bail against the orders of the U.S. government, Ver was sent to Mallorca, an island off the coast of Spain. Since then, authorities have been processing the U.S. extradition request, and a larger legal battle has ensued.

The Case against Roger Ver

The Department of Justice (DOJ) has charged Ver,1 in the Central District of California, with three counts of mail fraud under 18 U.S.C. § 1341, two counts of tax evasion under 26 U.S.C. § 7201, and three counts of making fraudulent or false statements under penalties of perjury under 26 U.S.C. § 7206(1). The charges are related to the preparing, mailing, and filing of his 2014 and 2017 non-resident alien income tax returns (1040NR), a 2016 gift tax return (Form 709), and his 2014 exit tax return (Form 8854). The allegations against Ver stem from activity from more than a decade ago, beginning in 2014 with Ver’s expatriation from the United States through 2018. Central to the case is a dispute on the valuation and ownership of an amount of bitcoin in 2014. If extradited, tried, and convicted, Ver faces 109 years in prison. Three charges of mail fraud—physically placing the alleged false documents in the mail—account for 90 of the 109 years.

While preparing, mailing, and filing his tax returns, Ver relied on an expert team of lawyers and tax advisors, including former federal prosecutors and former IRS agents. Ver maintains that he acted in accordance with the advice given to him by his legal counsel and that he is not guilty of the accusations against him. For years, Ver had always been clear: he was willing to pay the amount of tax owed. However, instead of informing Ver of what he owed, the U.S. government launched a criminal case against him, which the defense argues is based on selective quotation, a violation of Ver’s attorney-client privilege, and a number of other legal irregularities dating back to a time in which there was little to no guidance from the IRS on how to treat cryptocurrency (and when most bitcoin owners were not filing taxes on cryptocurrency at all). The accusations against Roger Ver should be understood in this context.

For clarity, Table 1 outlines each count against Ver and the corresponding dates and activity. Note that the information provided in the table is based on the indictment.2 MemoryDealers and Agilestar were Ver’s U.S.-based companies, for which he had to value and calculate the gains on their hypothetical sale as part of the exit tax for his expatriation. Given that Ver’s companies remained domiciled in the U.S. post-expatriation, he was still subject to U.S. tax on distributions and dividends received from those companies.

Table 1. Outline of the charges against Roger Ver

(Note: Information based on the indictment)

| Count | U.S. Code | Date(s) | Activity |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 18 U.S.C. § 1341 – mail fraud | May 4, 2016 | Mailing a false 2014 1040NR and Form 8854 to the IRS. |

| 2 | 18 U.S.C. § 1341 – mail fraud | July 19, 2016 | Mailing a second false 2014 1040NR and Form 8854 to the Department of Treasury of the IRS (after the IRS informed Return Preparer 1 it did not receive the forms sent on May 4, 2016). |

| 3 | 18 U.S.C. § 1341 – mail fraud | Dec. 15, 2018 | Mailing a false 2017 1040NR to the IRS. |

| 4 | 26 U.S.C. § 7201 – tax evasion | (Beginning in 2014 for each)May 4, 2016 | Filing a false 2011 Gift Tax Return, Form 709—Falsely claimed Ver gifted 25,000 bitcoins to his partner (not legally married wife) on November 15, 2011. |

| May 10, 2016 | Filing a false 2014 Form 8854—Failed to report personally owned bitcoins and underreported the fair market values of MemoryDealers and Agilestar. Filing a false 2014 1040NR—Failed to report gains from the constructive sale of personally owned bitcoin and underreported gains from the constructive sales of MemoryDealers and Agilestar. | ||

| July 22, 2016 | Filing a false 2014 1040NR—Failed to report gains from the constructive sale of personally owned bitcoin and underreported gains from the constructive sales of MemoryDealers and Agilestar. (This accusation is repeated twice since the IRS informed Return Preparer 1 it did not receive the 2014 1040NR that was sent on May 4, 2016. Ver re-signed the form and Return Preparer 1 sent it again on July 19, 2016, and it was received on July 22, 2016. The indictment omits the re-mailing of Form 8854 in this accusation.) | ||

| June 19, 2017 | Instructing Employee 1 to “close out” the books of MemoryDealers, which reported less than $10,000 in assets. | ||

| Dec. 18, 2018 | Filing a false 2017 1040NR—Failed to report income from the distributions of bitcoins to Ver from MemoryDealers and Agilestar. | ||

| 5 | 26 U.S.C. § 7201 – tax evasion | June 19, 2017 | Instructing Employee 1 to “close out” the books of MemoryDealers, which reported less than $10,000 in assets. |

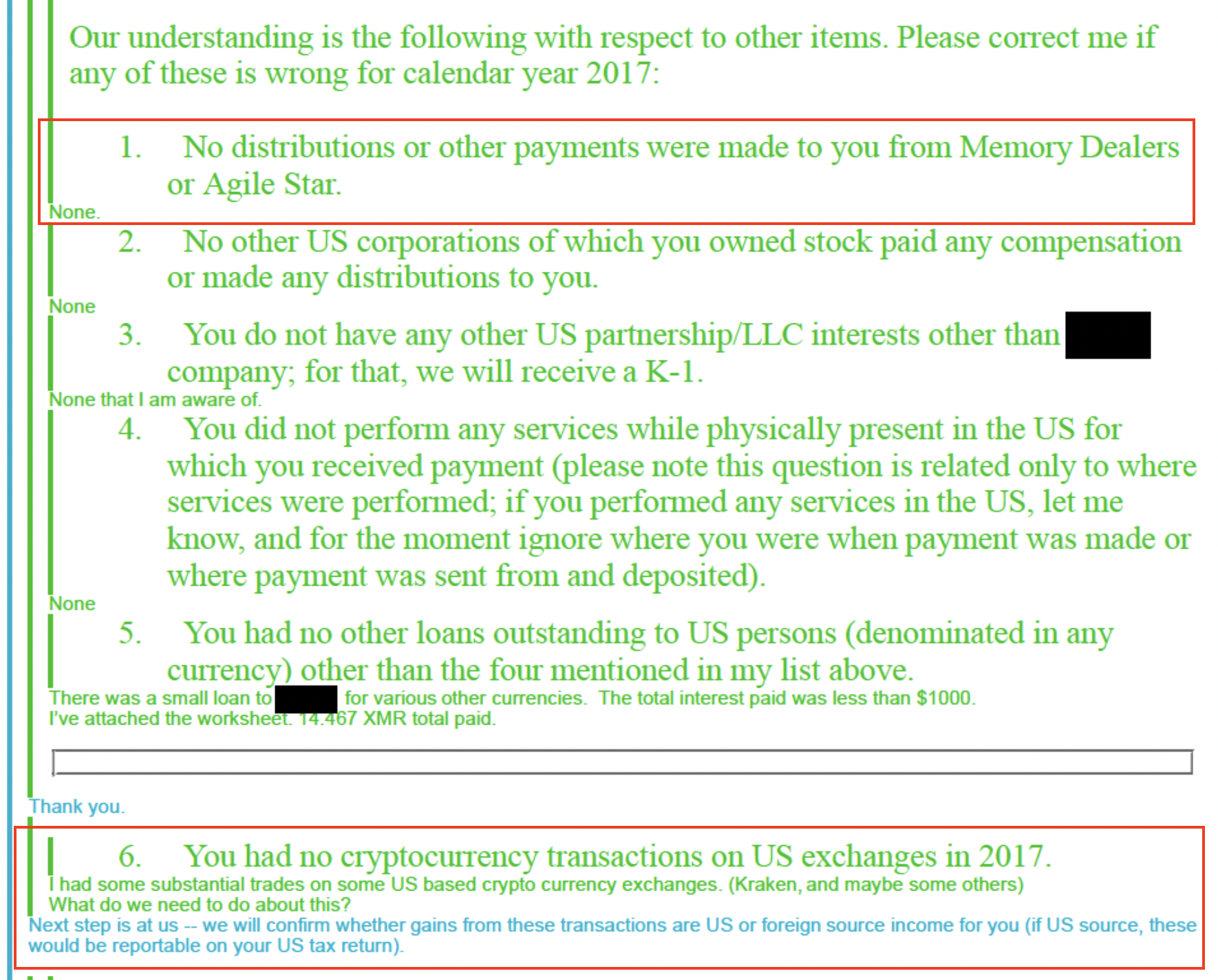

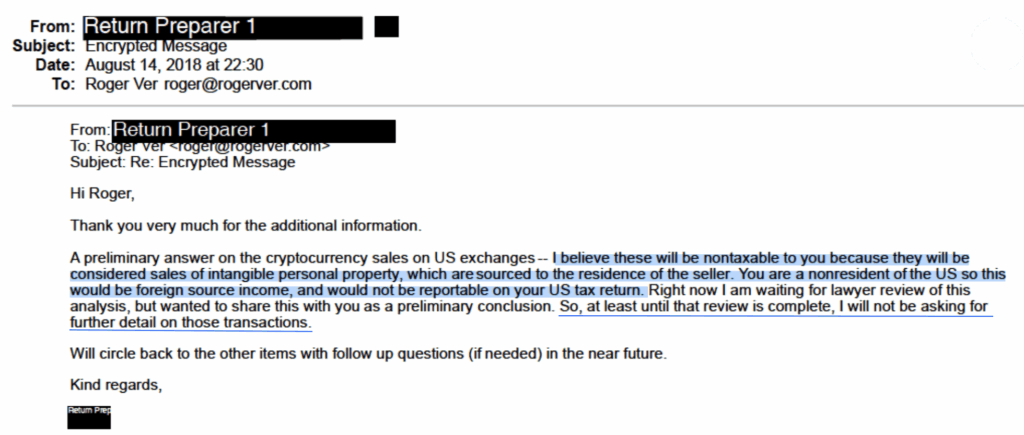

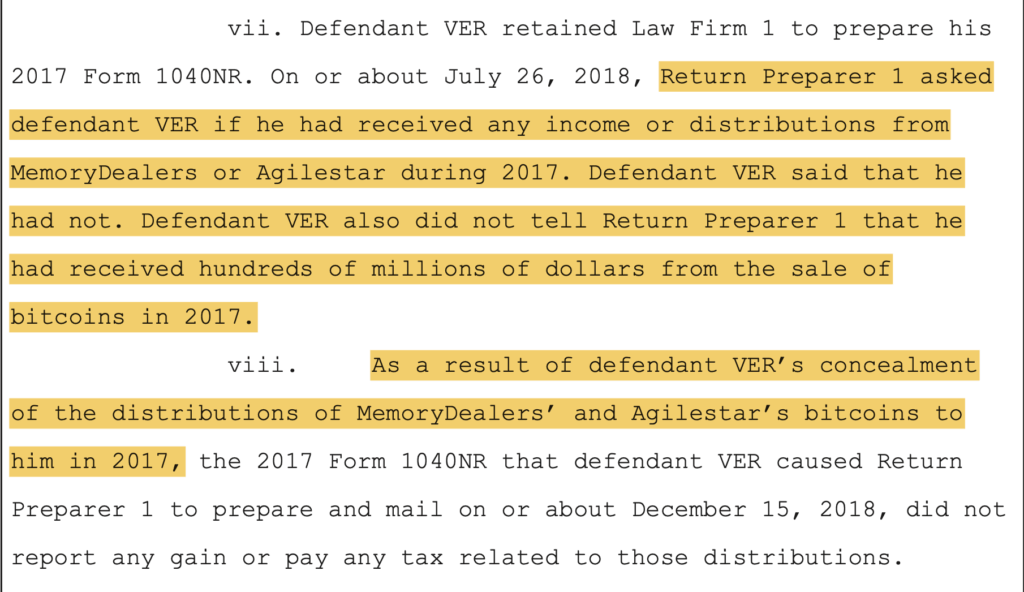

| July 26, 2018 | Falsely stating to Return Preparer 1 that he (Ver) did not receive any distributions or payments from MemoryDealers and Agilestar in 2017. | ||

| Dec. 18, 2018 | Filing a false 2017 1040NR—Failed to report income from the distributions of bitcoins to Ver from MemoryDealers and Agilestar. | ||

| 6 | 26 U.S.C. § 7206(1) – fraud/false statements (2014 Form 1040NR) | May 10, 2016 | Filing a false 2014 1040NR under penalties of perjury. Failed to report the gain from the constructive sale of personally owned bitcoin. Falsely reported the proceeds and gains from the constructive sales of MemoryDealers and Agilestar. |

| 7 | 26 U.S.C. § 7206(1) – fraud/false statements (2014 Form 8854) | May 10, 2016 | Filing a false 2014 8854 under penalties of perjury. Falsely reported net worth. Failed to report personally owned bitcoins and account at Coinbase. Falsely reported the fair market values of MemoryDealers and Agilestar. |

| 8 | 26 U.S.C. § 7206(1) – fraud/false statements (2017 Form 1040NR) | Dec. 18, 2018 | Filing a false 2017 1040NR under penalties of perjury. Falsely reported total tax, since it did not include any tax from the distributions of bitcoins to Ver from MemoryDealers and Agilestar. Falsely reported the amount owed. |

On December 3, 2024, Ver’s defense counsel filed a motion to dismiss counts one through eight of the indictment,3 citing the unconstitutionality of the exit tax, the government’s reliance on selective quotation presented to the grand jury, and the vague statutory foundations and lack of regulatory clarity on the tax treatment of cryptocurrency, which forms the basis of the government’s case. Attached to the filing were Exhibits 1-14, which include email communications among Ver and the members of his legal and tax counsel, spanning a period from 2012 to 2018. The defense argues these communications, when understood in full, decimate the accusations that Ver acted willfully to violate U.S. tax law (see case timeline for details).

An Armed Raid, Violation of DOJ Protocol

Additionally, in its motion to dismiss, the defense argues that during the course of the investigation into Ver, special agents of the IRS Criminal Investigation Division violated Ver’s attorney-client privilege when they conducted an unannounced raid on his tax counsel and engaged in an interview with one of Ver’s attorneys prior to issuing subpoenas in December 2017.

According to the defense, “Department policy requires significant scrutiny by Department supervisors and safeguards against abuse prior to the questioning of a subject’s attorney or the service of compelled process on an attorney (Justice Manual § 9- 13.410).” The defense further argues that the interrogation “prior to the service of compelled process” indicates this investigative technique likely does not adhere to official Department policy.

Furthermore, following the issuance of grand jury subpoenas to Ver’s tax counsel, a legal dispute ensued over access to Ver’s privileged communications. The dispute went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court in a case called In re Grand Jury.4 After hearing oral arguments, the U.S. Supreme Court ultimately dismissed the case, thus granting the IRS access to Ver’s privileged communications in 2023.

Legal Experts Weigh In

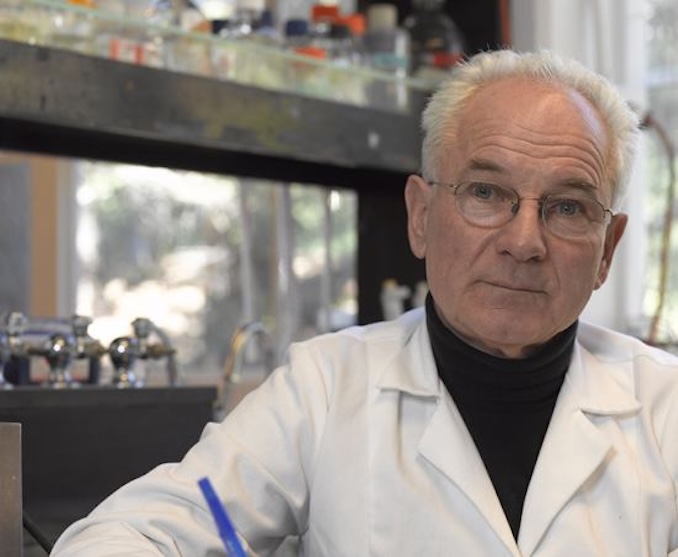

With Roger Ver’s prominence as a businessman, author, and philanthropist,5 his case has garnered much attention from the crypto community and the public at large, including professionals in the field of tax law. American international tax lawyer Attorney Anthony Parent,6 who has been following the case and has extensive experience assisting clients with expatriation and filing Form 8854, says Roger Ver and his legal team did everything correctly.7 “I have sympathy for the law firm because they did everything right and they went through everything the way I would go through it,” said Attorney Parent. “This is totally a political indictment.”

Criminal tax lawyer Attorney Robert Barnes8 has been particularly vocal about the U.S. government’s deviation from the proper protocols in its pursuit of Ver. “Normal procedure is to go through civil collections first, not rush to criminal prosecution,” said Attorney Barnes. “Normal procedure is to tell someone how much tax they believe is due, not hide it from the individual even when he asks for an amount” (as Ver repeatedly did with no answer).

Reiterating a similar sentiment, Attorney Parent says this case may not really be about taxes but rather fear and intimidation, especially to prevent people from expatriating. “The government looks at people who are expatriating as ‘we’re going to lose out on those estate taxes’ and so essentially the exit tax is a stand-in for the estate tax because from the government’s perspective they are going to lose you once you expatriate.”

Some may be left to now wonder, how complicated is the expatriation process? And why would someone like Roger Ver choose to expatriate from the United States in the first place? Although only Ver himself can answer such a question, he has previously expressed that the decision was a difficult one9 and that America will always be “near and dear to [his] heart.” However, like for many others, it was a decision based on the realization that he had no other choice.

The Expatriation Process

[Author’s note: This section is a simplified explanation of the expatriation procedure and its tax implications. For more detailed analyses, visit the work of Attorney John Richardson,10 who contributed to this section. ]

The 14th Amendment11 makes clear that an individual born or naturalized in the United States is a U.S. citizen. However, the 14th Amendment speaks only to which individuals have a constitutional right to U.S. citizenship; it does not address whether or how U.S. citizenship can be relinquished.

U.S. citizens can relinquish their citizenship in a process called expatriation. It is important to understand expatriation as an immigration and citizenship issue that may trigger significant tax implications. The immigration-related procedure of expatriation is governed under the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA),12 whereas the tax implications that may follow expatriation are separately governed under the Internal Revenue Code (IRC).

INA Section 349A lists seven possible expatriating or relinquishing acts that may potentially result in the loss of U.S. citizenship:

(1) obtaining naturalization in a foreign state upon his own application or upon an application filed by a duly authorized agent, after having attained the age of eighteen years; or

(2) taking an oath or making an affirmation or other formal declaration of allegiance to a foreign state or a political subdivision thereof, after having attained the age of eighteen years; or

(3) entering, or serving in, the armed forces of a foreign state if (A) such armed forces are engaged in hostilities against the United States, or (B) such persons serve as a commissioned or non-commissioned officer; or

(4) (A) accepting, serving in, or performing the duties of any office, post, or employment under the government of a foreign state or a political subdivision thereof, after attaining the age of eighteen years if he has or acquires the nationality of such foreign state; or (B) accepting, serving in, or performing the duties of any office, post, or employment under the government of a foreign state or a political subdivision thereof, after attaining the age of eighteen years for which office, post, or employment an oath, affirmation, or declaration of allegiance is required; or

(5) making a formal renunciation of nationality before a diplomatic or consular officer of the United States in a foreign state, in such form as may be prescribed by the Secretary of State; or

(6) making in the United States a formal written renunciation of nationality in such form as may be prescribed by, and before such officer as may be designated by, the Attorney General, whenever the United States shall be in a state of war and the Attorney General shall approve such renunciation as not contrary to the interests of national defense; or

(7) committing any act of treason against, or attempting by force to overthrow, or bearing arms against, the United States, violating or conspiring to violate any of the provisions of section 2383 of title 18, or willfully performing any act in violation of section 2385 of title 18, or violating section 2384 of title 18 by engaging in a conspiracy to overthrow, put down, or to destroy by force the Government of the United States, or to levy war against them, if and when he is convicted thereof by a court martial or by a court of competent jurisdiction.

The first four actions occur outside a U.S. Consulate. The fifth form of relinquishment, “renunciation,” takes place inside a U.S. Consulate under the direction of a U.S. Consular Officer. The sixth and seventh acts are beyond the scope of this article.

Note that the statute speaks of “relinquishing” U.S. citizenship. “Renunciation” is one of seven forms of relinquishment. Taking the oath of renunciation is one of seven expatriating acts that results in the relinquishment of U.S. citizenship. Often, renunciation and relinquishment are used interchangeably, but this is incorrect. One may relinquish U.S. citizenship without renouncing U.S. citizenship. That said, a renunciation of U.S. citizenship is a relinquishment of U.S. citizenship. Additionally, taking an oath of renunciation may have its own immigration-related consequences. (Note: The 1996 Reed Amendment may prohibit some expatriates from re-entering the United States if the individual took an oath of renunciation of U.S. citizenship for tax avoidance purposes.13)

Thus, if one voluntarily commits any one of the above acts with the specific intention of relinquishing U.S. citizenship, the individual may seek a Certificate of Loss of Nationality (CLN) from the U.S. State Department. This request is supported by submitting a signed Request for a Determination of Possible Loss of Citizenship (Form DS-4079) to a U.S. Embassy or Consulate. The request for a CLN takes place in the context of an interview. If the request is approved, the U.S. Government will issue a CLN, and the individual will cease to be a U.S. citizen for immigration purposes under the INA. (Note that the process of “renouncing U.S. citizenship,” because it takes place under the direction of a U.S. Consular Officer, is an automatic request for a CLN.)

Roger Ver, after voluntarily naturalizing as a citizen of St. Kitts and Nevis on February 4, 2014, formally requested a CLN at the U.S. Consulate in Barbados on March 3, 2014.

While the court documents do not provide sufficient clarity, Ver’s claim for a CLN appears to have been based on INA 349(a)(1):

“[O]btaining naturalization in a foreign state upon his own application or upon an application filed by a duly authorized agent, after having attained the age of eighteen years.”

In other words, Ver’s naturalization as a St. Kitts and Nevis citizen was the expatriating act that led to Ver’s relinquishment of U.S. citizenship. However, naturalizing as a citizen of St. Kitts and Nevis is a relinquishing act only under the INA and thus only impacts Ver’s citizenship/immigration status. It did not terminate his status as a U.S. taxpayer.

This is confirmed by 7701(a)(50) of the IRC14:

(50) Termination of United States citizenship

(A) In general

An individual shall not cease to be treated as a United States citizen before the date on which the individual’s citizenship is treated as relinquished under section 877A(g)(4).

This means that Ver still had to meet separate and additional notification requirements in 877A(g)(4) of the Internal Revenue Code (IRC) to ensure he was no longer treated as a U.S. citizen for the purposes of U.S. taxation, reporting, and penalties.

To reiterate, committing one of the seven expatriating acts results in the relinquishment of U.S. citizenship for immigration and nationality purposes. The subsequent receipt of a CLN is proof that the U.S. government has been notified of and accepts the relinquishment of citizenship under the Immigration and Nationality Act. According to the IRC, as shown above, the individual shall continue to be treated as a U.S. citizen for U.S. tax purposes until his or her citizenship is considered relinquished under Internal Revenue Code 877A(g)(4). (This point will be revisited in greater detail in the context of Ver’s case.)

A Brief History of Relinquishment and and Taxation

Throughout most of U.S. history, U.S. citizenship has been tied to taxation. The United States is one of only two countries in the world that employ citizenship-based taxation.15 Under the U.S. citizenship taxation regime, U.S. citizens are subject to U.S. taxation on their worldwide income wherever they live in the world and wherever the source of the income. U.S. residents are also subject to U.S. taxation on their worldwide income. Green card holders are subject to the same rules. Today, U.S. citizens (and residents, including green card holders) living outside the United States are required to file and may owe U.S. tax on their worldwide income. The only way to avoid this is to relinquish U.S. citizenship or abandon one’s green card.

Since 1966,16 there have been tax consequences for expatriation with the establishment of IRC Section 877 by the Foreign Investors Tax Act.17 However, the rules have evolved since then. This section focuses on two specific periods which are relevant to Ver’s situation.

Expatriation: June 3, 2004 – June 16, 2008

The American Jobs Creation Act (AJCA) of 200418 amended sections 877 and 6039G of the Internal Revenue Code, which defined the expatriation tax and reporting rules. Amended Section 877 imposed an “alternative tax regime” on some expatriated individuals.19 Amended Section 6039G imposed additional reporting requirements for all expatriating individuals each year they are subject to Section 877. The new policies were effective from June 3, 2004, and remained in effect until June 16, 2008.

Prior to June 3, 2004, expatriation for tax purposes followed expatriation for immigration purposes. Thus, citizenship for purposes of U.S. taxation was based on citizenship for immigration/nationality. The Internal Revenue Code determination of one’s citizenship for the purposes of U.S. taxation was based only on immigration/citizenship law.

However, this changed with the implementation of IRC 7701(n) found in section 804 of the AJCA 2004.

‘‘(n) SPECIAL RULES FOR DETERMINING WHEN AN INDIVIDUAL IS NO LONGER A UNITED STATES CITIZEN OR LONG-TERM RESIDENT.—An individual who would (but for this subsection) cease to be treated as a citizen or resident of the United States shall continue to be treated as a citizen or resident of the United States, as the case may be, until such individual—

‘(1) gives notice of an expatriating act or termination of residency (with the requisite intent to relinquish citizenship or terminate residency) to the Secretary of State or the Secretary of Homeland Security, and

‘(2) provides a statement in accordance with section 6039G.’’

IRC 7701(n) effectively created the “tax citizen.” As an expatriation lawyer specializing in citizenship renunciation and green card abandonment, Attorney John Richardson has described the practical impact of the new 7701(n) as creating dual U.S. citizenship for all U.S. citizens:

“All of a sudden, all Americans got dual citizenship. You were a citizen for immigration purposes, and because it’s the greatest, best citizenship of all [irony], you get a new form of citizenship called tax citizenship.”

IRC 7701(n) required an expatriated individual to continue to be treated as a U.S. citizen for tax purposes (meaning taxes, reporting, and penalties continue) until he or she separately notified the IRS of his or her expatriation by filing Form 8854 (Initial and Annual Expatriation Statement). (The same conditions applied for noncitizen long-term residents of the United States, or green card holders. Until filing Form 8854 and notifying the Department of Homeland Security of termination of U.S. residency, former noncitizen long-term residents would still be treated as U.S. residents for tax purposes.) Form 8854 requires a relinquisher to disclose all property, assets, and worldwide income as well as certify tax compliance for the five years prior to expatriation. As John Richardson has remarked:

“And they should have had ads all over the country on billboards saying, ‘Coming June 3, 2004! The more abusive form of U.S. Citizenship!’”

During this time period, in a sense, one had to relinquish U.S. citizenship twice in order to avoid tax obligations—once for immigration purposes with the State Department (DS-4079) and then again for tax purposes with the IRS by filing Form 8854. Says Richardson:

“You could lose your U.S. citizenship for immigration purposes and never be allowed in the United States. They can tell you, ‘Get lost. Get back on the plane. We’ll send you back in cargo. We care so little about you.’ But what they do care about is this—that by God, you keep filing U.S. tax returns as a U.S. resident until you submit that 8854!”

Therefore, in summary, beginning June 3, 2004, and continuing today, regardless of one’s status as a U.S. citizen under U.S. immigration law, one may still be treated as a U.S. citizen for tax purposes. Determining citizenship for tax purposes is different from determining citizenship for immigration/nationality purposes.

Expatriation: June 17, 2008 to present

In 2008, the Heroes Earnings Assistance and Relief Tax (HEART) Act repealed the AJCA 2004.20 Section 30121 of the HEART Act made three changes to the expatriation process:

- First, it added Section 877A to the IRC, which imposed an exit tax on “covered expatriates” who relinquished U.S. citizenship on or after June 17, 2008.

- Second, it added Section 2801 to the IRC, which made the recipients of gifts or bequests from “covered expatriates” subject to a tax on receipt of the gift or bequest.

- Third, it removed the requirement of filing Form 8854 as a condition to ending treatment as a U.S. citizen for tax purposes. In simple terms (as long as a CLN was issued), one ceased to be treated as a U.S. citizen for tax purposes on the date of the renunciation appointment at the U.S. Consulate.

An individual is a “covered expatriate” and thus subject to the Section 877A rules and the 2801 “covered gift” rules if he or she meets any one of the following three criteria:

- An average annual net income tax greater than $205,000 (adjusted for inflation annually) for the five years prior to expatriation, or

- A net worth of $2 million or more on the date of expatriation, or

- Failure to complete Form 8854 and/or failure to confirm tax compliance for the five years prior to the date of expatriation

Given that Ver had a net worth of more than $2 million on the date of expatriation in 2014, he was considered a “covered expatriate” and thus subject to both the 877A Exit Tax and 2801 “Covered Gift” rules.

It is important to note that all expatriates, regardless of status, are required to complete and file Form 8854 in order to avoid “covered expatriate” status. This is because Form 8854 is where the IRS requires that one certify the five years of tax compliance. Failure to complete Form 8854 results in a $10,000 penalty (in addition to “covered expatriate” status). However, unlike the policy from June 3, 2004, to June 16, 2008, failure to complete Form 8854 does not result in one continuing to be treated as a U.S. citizen for tax purposes.

The primary impact of the June 16, 2008, legislation is that “covered expatriate” status (subject to minor exceptions) has the effects of (1) making the person subject to the 877A exit tax rules and (2) making the person’s heirs subject to the 2801 “covered gift” rules.

The Cost of Being Rich

For nearly 60 years, the United States has imposed a tax on certain expatriating individuals, but it was not until 2008 that the “exit tax” was imposed. The “exit tax” is a collection of different types of taxes triggered by relinquishment of U.S. citizenship or abandonment of the green card. It includes (but is not limited to) a tax based on a “deemed” (not actual) sale of property on the date prior to expatriation.

In Section 877A, for the purposes of calculating the exit tax, “covered expatriates” are deemed to have sold all of their property on the day before expatriation for its fair market value. For example, if one’s date of expatriation for tax purposes under IRC 877A(g)(4) was April 30, 2025, he or she would calculate the hypothetical sale of all property as of April 29, 2025. Any gain or loss arising from that hypothetical sale shall be taken into account for that taxable year prior to expatriation. Thus, the exit tax is an unrealized capital gains tax, as the individual is required to pay tax on a sale that did not occur and gains that were never realized. Four of the eight charges against Ver are related to his exit tax calculation.

While all “covered expatriates” are subject to the exit tax, not all “covered expatriates” will owe an exit tax. There is such a thing as expatriation planning, said Attorney Richardson. One could plan for expatriation over a period of several years if one anticipates significant taxable capital gains. “Gradually, you can sell things and create a situation where on the day that you relinquish, you are subject to the exit tax but because there is no gain, you’re not going to pay an exit tax.”

Additionally, there is a dual citizenship at birth exemption by which one may avoid “covered expatriate” status (and the exit tax and covered gift rules) if he or she meets certain criteria. Attorney Richardson describes an example of two individuals seeking to relinquish—both individuals have acquired the same amount of wealth under identical circumstances, but one has a French citizen father and thus acquired French citizenship at birth, whereas the other individual has two U.S. citizen parents and did not acquire a second citizenship at birth. Despite having the same amount of wealth, the person with the French citizen father can be exempt from the “covered expatriate” designation while the other individual, with two American parents, who did not acquire dual citizenship at birth, may meet the conditions to be a “covered expatriate.” Attorney Richardson comments:

“Imagine exempting a group of people from ‘covered expatriate’ status not because of anything to do with their own actions but because of who their father or their mother was.”

While seemingly arbitrary, Attorney Richardson says this may be understood as non-taxation based on citizenship. This would explain the dual citizen from birth exemption as an extension of citizenship-based taxation:

“If you see citizenship as an ownership interest that the state has in the individual, then I think it’s very easy to see dual citizenship as dual ownership.”

Date of Relinquishment for Tax Purposes

As reiterated throughout this report, relinquishment of U.S. citizenship for immigration purposes and tax purposes are treated separately. Recall that according to the current law under IRC 7701(a)(50),14 it states:

(50) Termination of United States citizenship

(A) In general

An individual shall not cease to be treated as a United States citizen before the date on which the individual’s citizenship is treated as relinquished under section 877A(g)(4).

According to section 877A(g)(4) of the IRC22:

“(4) Relinquishment of citizenship

A citizen shall be treated as relinquishing his United States citizenship on the earliest of—

(A) the date the individual renounces his United States nationality before a diplomatic or consular officer of the United States pursuant to paragraph (5) of section 349(a) of the Immigration and Nationality Act (8 U.S.C. 1481(a)(5)),

(B) the date the individual furnishes to the United States Department of State a signed statement of voluntary relinquishment of United States nationality confirming the performance of an act of expatriation specified in paragraph (1), (2), (3), or (4) of section 349(a) of the Immigration and Nationality Act (8 U.S.C. 1481(a)(1)–(4)),

(C) the date the United States Department of State issues to the individual a certificate of loss of nationality (CLN), or

(D) the date a court of the United States cancels a naturalized citizen’s certificate of naturalization.

Subparagraph (A) or (B) shall not apply to any individual unless the renunciation or voluntary relinquishment is subsequently approved by the issuance to the individual of a certificate of loss of nationality by the United States Department of State.”

Therefore, in the case of Roger Ver, his date of expatriation for tax purposes, and thus the date he was required to use for calculating the exit tax, is the date on which he furnished to the U.S. State Department (March 3, 2014) a signed statement of voluntary relinquishment of U.S. nationality, confirming he committed an expatriating act found in INA 349A. In Ver’s case, the expatriating act was likely naturalizing as a St. Kitts and Nevis citizen (on February 4, 2014), which falls under INA 349A(1).

While Ver’s CLN states the date of expatriation as February 4, 2014, that is only relevant for immigration purposes. The date on which he expatriated for tax purposes was the date on which he notified the U.S. Consulate in Barbados (on March 3, 2014) of his committing an expatriating act. For the period between Ver’s committing the expatriating act and notifying the Consulate, albeit brief, he was still to be treated as a U.S. citizen.

Ver’s lawyers incorrectly advised him to calculate the exit tax based on February 4, 2014, which was the date listed on the CLN. The correct date was March 3, 2014, which was the date of notification of the expatriating act. While this has led to confusion, this discrepancy does not have a significant impact on the case, and Ver is not penalized for this error.

In the motion to dismiss, to put it simply, the defense claims the exit tax itself is unconstitutional, arguing it is tax on unrealized capital gains and that it infringes on the fundamental right to expatriate. The U.S. government, in its opposition to the motion to dismiss, argues there is no fundamental right to expatriate and that a tax on unrealized gains is constitutional. This matter is still being litigated.

Following Ver’s expatriation, his companies, MemoryDealers and Agilestar, by operation of law, converted from S-corporations to C-corporations. Both companies retained their status as “U.S. Persons” in the United States. As a result, Ver (regardless of his citizenship) was subject to U.S. tax on distributions and dividends received from those companies. Four of the eight charges against Ver are related to the preparing, filing, and mailing of his 2017 Form 1040NR, which was his nonresident alien tax return and was related to distributions from his U.S. companies. Notably, the 2017 tax issues are unrelated to his final expatriation return filed earlier.

Case Timeline

The following is a timeline of the relevant events in the case of Roger Ver, spanning nearly 25 years. The timeline compiles information from court documents submitted by the prosecution and defense as well as material in the public domain.

The timeline is organized into four sections:

- Ver’s early professional life (1999–2010)

- The time period which forms the basis of the allegations (2011–2018)

- The continued investigation into Ver (2019–2023)

- The current developments in the case (2024–2025)

Note: Exhibits 1-14, referenced in this timeline, are not necessarily in chronological order. For example, an exhibit with a higher number may reference emails from a time period that predates an exhibit with a lower number.

I. Roger Ver’s Early Professional Life (1999–2010)

1999: While attending De Anza College, Roger Ver founds MemoryDealers, a California-based computer equipment company. Ver serves as the CEO of MemoryDealers until its dissolution around 2017.

2000: Ver runs for California State Assembly23 (District 28) as a Libertarian at the age of 21.

During the fall of 2000, as part of the campaign, Ver participates in a debate at San Jose State University against the Republican and Democratic candidates. During the debate, Ver criticizes the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms (ATF) and the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) for killing children in the Waco, Texas, siege in April 1993.

In the documentary Bitcoin Jesus: The Prosecution of Roger Ver,24 Ver reflects on this moment. “I called the ATF and FBI a bunch of jackbooted thugs and murderers, in reference to murdering children in Waco, Texas.”

Unbeknownst to Ver, ATF and FBI agents were present in the audience during the debate. In the documentary, legal advocate Tracy Thurman says this marked a significant moment in Ver’s life. “For Roger, that was the beginning of asking very serious questions about the U.S. government,” said Thurman. “And honestly, it was the beginning of the persecution against him.”

At this time, Ver’s businesses were kicking off, and he had begun making a name for himself as a young libertarian promoting the values of financial freedom and non-interventionism.

June 12, 2001: An ATF agent files a criminal complaint against Ver in the Northern District of California25 for selling “pest control report 2000” (PCR 2000) on eBay without a license. PCR 2000 is a type of firework used by farmers to scare birds out of their fields. At the time, eBay had a guns and ammo section, and many people were selling this item without a license. However, Ver states he was the only person to be prosecuted.

The ATF agent who filed the complaint against Ver, Micah Wellman, spoke with Taylor Hudak (the author of this report) and responded to questions on the case and investigation. His responses may be read, in part, here.26

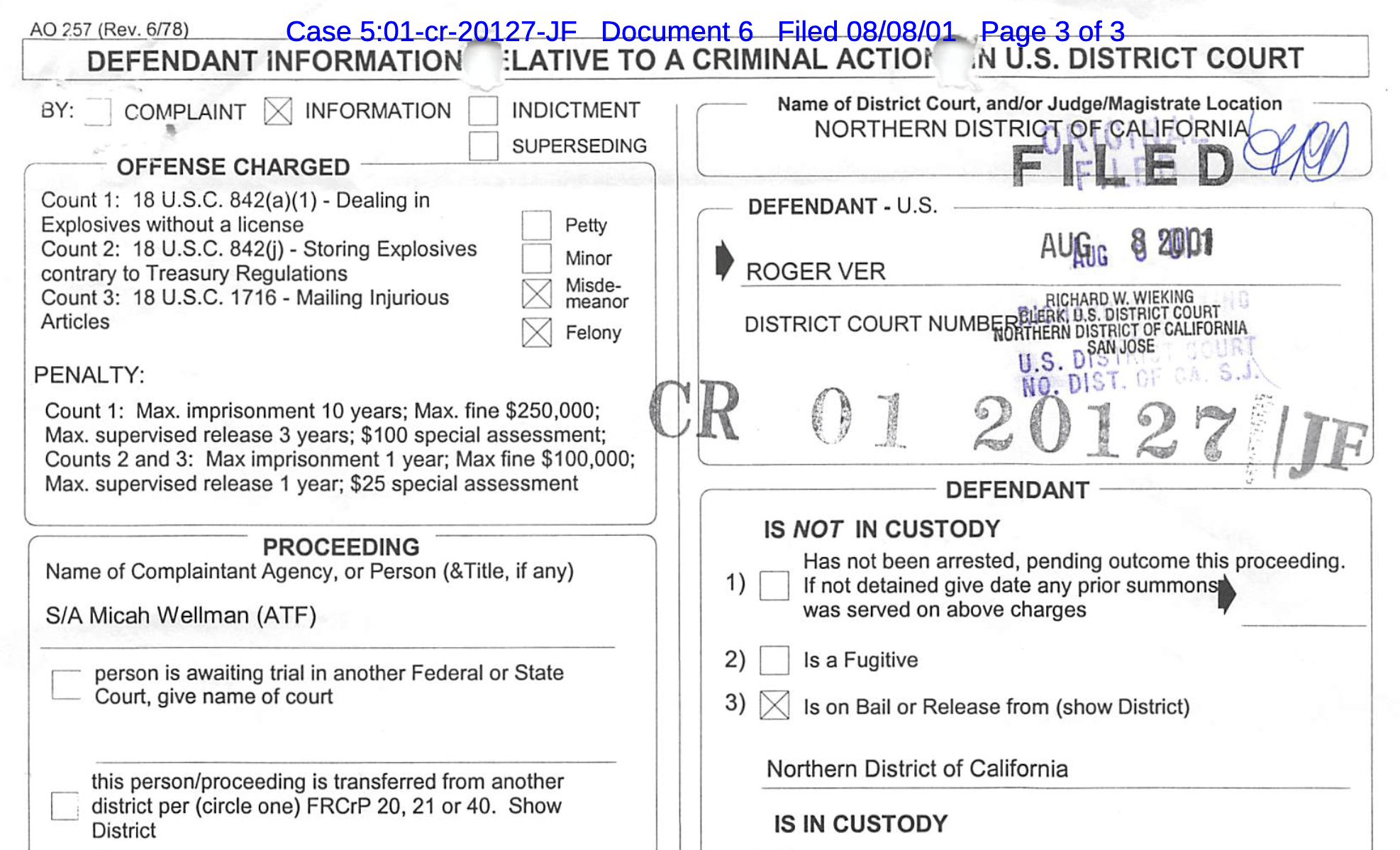

August 8, 2001: Ver is charged with three counts,27 including Dealing in Explosives Without a License, Illegally Storing Explosives, and Mailing Injurious Articles in relation to selling PCR 2000 on eBay without a license. The charges stem from activity from approximately 1998–2000. If tried and convicted, Ver faces 10 years in prison.

Notably, Robert S. Mueller III was the U.S. Attorney for the Northern District of California at the time and is listed on the indictment.

At some point during Ver’s prosecution, a meeting takes place with Ver, Ver’s attorney, two ATF agents, and the prosecutor.28 At the meeting, Ver’s attorney addresses the prosecutor, seeking reassurance that this is the type of case in which the state would typically impose a fine and encourage the defendant to get a license but would not impose imprisonment. However, at that point, one of the ATF agents pounds his fist on the table and says, “But you didn’t hear what he said about us.” This is in reference to Ver’s criticism of the ATF (and FBI) during the 2000 California State Assembly debate at San Jose State University.

October 2001: Ver enters a plea agreement of guilty on all three counts related to the selling and distribution of PCR 2000.29

May 2, 2002: At a hearing30 before Judge Jeremy Fogel,31 Ver is sentenced to 10 months in prison and a $2,000 fine. Upon serving his sentence, Ver is given a three-year period of supervised release.

August 2, 2002: Ver begins serving his 10-month prison sentence.

May 6, 2003: Ver is released from prison. During the next three years, he must not leave the United States as he is subject to a three-year period of supervised release.

June 3, 2004: The American Jobs Creation Act (AJCA) of 2004 amends sections 877 and 6039G of the Internal Revenue Code (IRC), which defined the expatriation tax and reporting rules. Individuals expatriating on or after this date (until June 16, 2008) are required to complete Form 8854 to cease to be treated as a U.S. citizen. (See expatriation section for more details.)

July 15, 2005: Ver founds Agilestar, a company that sells computer equipment. Ver serves as CEO until the company’s dissolution around 2017.

2006: Ver moves to Japan on the first day he is legally permitted to leave the United States (at the conclusion of his three-year period of supervised release). Ver then lives in Japan for several years and rarely returns to the United States.

In an interview,32 Ver recalls that from the moment he left the United States, he had a desire to relinquish his U.S. citizenship. However, it was not until 2011 that he was in a position to begin the expatriation process.

October 28, 2007: In the early morning hours, criminals break into Ver’s business office in Santa Clara, CA, by crashing a U-haul truck into the front door of the business. More than $1 million worth of computer parts and equipment is stolen. Ver contacts the police to file a report.

Two weeks later, a company in Los Angeles calls Ver’s business and tries to resell him the stolen parts. Ver reports this to law enforcement, including the Santa Clara Police Department, the Los Angeles Police Department, and the FBI. However, the authorities do nothing.

To prevent another break-in, Ver spends a significant amount of money on security equipment for his office building. Shortly after installing the equipment, the local fire and police departments notify him that he is not permitted to have this type of security and he must undo the measures or his business will be forced to close down.

This is one example of several similar incidents that happened to Ver during this time period. Ver recalled this specific occasion in an interview.33

June 17, 2008: The Heroes Earnings Assistance and Relief Tax (HEART) Act repeals the AJCA 2004. Section 301 of the HEART Act makes several changes to the expatriation process, including the imposition of the exit tax on “covered expatriates.” (See expatriation section for more details.)

January 3, 2009: Bitcoin is launched.

II. Activity Subject to Prosecution (2011-2018)

2011

2011: Ver discovers Bitcoin while the price is still under $1. At this time, Ver promotes the use of Bitcoin and is enthusiastic about its potential to allow for financial freedom. Meanwhile, the mainstream perception of cryptocurrency is one of uncertainty, and there are no rules or guidance from the IRS on how to treat it for accounting or tax purposes.

According to the 2024 indictment, around April 2011, on behalf of MemoryDealers, Ver opens accounts on several cryptocurrency exchanges, including Mt. Gox. Ver wires funds from MemoryDealers’ and Agilestar’s bank accounts to Mt. Gox to purchase bitcoin for the companies. Ver and his companies begin acquiring bitcoin, which becomes an integral part of his businesses.

November 15, 2011: Ver gifts 25,000 bitcoin to his partner (a Japanese citizen). This is the date listed on Ver’s 2016 Form 709 (United States Gift—and Generation-Skipping Transfer—Tax Return).34

2012

Ver hires Law Firm 1 to advise and assist him with his formal expatriation from the United States. At the advice of Law Firm 1, Ver hires Appraiser 1, a “large international accounting firm,” to assist with the valuation of MemoryDealers and Agilestar.

June 2012: According to the 2024 indictment, Ver opens an account on Bitstamp (cryptocurrency exchange) on behalf of MemoryDealers. Ver wires funds from MemoryDealers’ bank account to Bitstamp to purchase bitcoin.

July 2012 – present: Ver co-founds blockchain.com.

July 23, 2012: According to the indictment, Ver opens an account with Coinbase, another cryptocurrency exchange.

August 6, 2012: Exhibit 2 is an email from Law Firm 1 to Roger Ver,35 in which Law Firm 1 lays out a detailed plan for Ver’s expatriation and exit tax preparations.

In the email, Law Firm 1 explains to Ver that he must calculate his exit tax by pretending to sell all of his assets on the day before expatriation. As part of that process, Law Firm 1 recommends Ver get appraisals of his assets. Law Firm 1 states, “We want to do this right. The objective is to exit the USA cleanly.” The email goes on to outline other expatriation-related issues such as the restructuring of Ver’s businesses, contacting an embassy, etc.

August 2012: According to the indictment, Ver engages Appraiser 1, who subsequently begins preparing draft valuations of MemoryDealers and Agilestar. Appraiser 1 advises that the bitcoins listed as assets of the companies “should be valued at their current market price.”

October 2012: According to the indictment, Ver provides Law Firm 1 with a list of his assets, which did not include bitcoin.

November 2012: MemoryDealers launches Bitcoinstore.com. Ver serves as CEO until its dissolution in July 2014.

2013

April 12, 2013: According to the indictment, Ver tells Appraiser 1 that he controls 25,000 bitcoins. The U.S. government alleges approximately 117,000 bitcoins were attributable to Ver and his companies at this time.

Note: The U.S. government’s accusations regarding the number of bitcoins attributable to Ver are based on a cluster analysis and other attribution evidence.

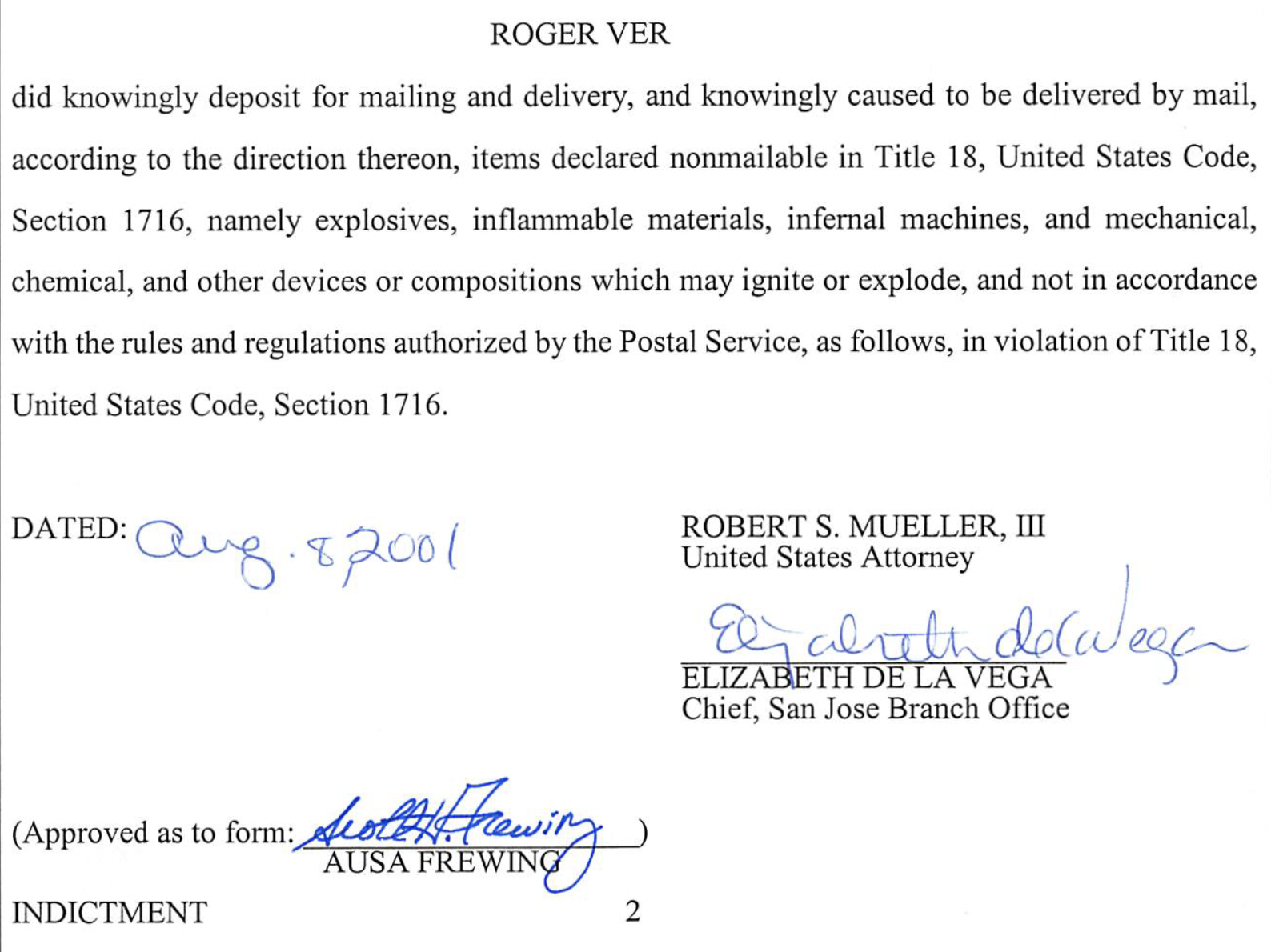

April 26, 2013 – December 8, 2013: Exhibit 1 is an email exchange between Ver, Lawyer 1/Law Firm 1, Appraiser 1, Return Preparers 1-3, and Employee 1.36 Ver and his team discuss his relinquishment of U.S. citizenship and its tax implications, including the complexities of reporting his bitcoin holdings, real estate, and other businesses.

In an email sent by Ver to his team on April 26, he states, in part, the following:

“I want to make sure that my exit tax payments are as clean as possible, with no room to have trouble from the IRS in the future…. I’m also very concerned about the proper way to handle my/Memorydealers’ bitcoin holdings…. I will definitely need everyone’s help in regards to this, since I have no idea what the IRS will be demanding of me.”

May 15, 2013: According to the indictment, Ver informed Appraiser 1 that he would not be expatriating soon and, therefore, Appraiser 1 did not finalize the valuations.

November 30, 2013: According to the indictment, Ver donated 1,000 of his personally held bitcoins to a charity qualified under section 501(c)(3) of the IRC.

December 6-8, 2013 (from Exhibit 1): Ver notifies his team that while the process of obtaining another citizenship has taken longer than expected, he is likely to naturalize as a St. Kitts and Nevis citizen very soon. Ver states he would like to promptly continue with the expatriation process.

2014

Ver retains Law Firm 1 to assist with his expatriation, including calculating his estimated exit tax payment. For perspective, the world of cryptocurrency at this time would be unrecognizable today, as the industry was very small and there was little guidance on how to treat cryptocurrency for tax purposes. Despite this, Ver is one of the first people to report and pay taxes on bitcoin.

In February, Mt. Gox, the largest cryptocurrency exchange at the time, files for bankruptcy and closes down. This is a significant and devastating moment in Bitcoin history. Additionally, this presents a serious difficulty for Ver when valuing his bitcoin holdings and calculating his exit tax, because there is no other exchange on which Ver can pretend to sell his bitcoin.

February 3, 2014: Law Firm 1 incorrectly advises Ver to use this date when calculating his exit tax.

February 4, 2014: Ver naturalizes as a St. Kitts and Nevis citizen. (This is the date listed on Ver’s CLN.)

March 2, 2014: This is the correct date for Ver’s exit tax calculation.

March 3, 2014: Ver submits a Request for a Determination of Possible Loss of Citizenship (Form DS-4079) to the U.S. Consulate in Barbados. The document includes a separately signed Statement of Voluntary Relinquishment of U.S. Citizenship. The State Department subsequently issues Ver a CLN that lists Ver’s expatriation date as February 4, 2014.

Because Ver ceases to be a U.S. citizen on this date (March 3, 2014), for tax purposes, his companies, MemoryDealers and Agilestar, both based in Santa Clara, CA, for which he is the sole owner and CEO, automatically convert from S-Corporations (small business corporations) to C-Corporations.

Following expatriation, Ver continues to be audited by the IRS.

March 25, 2014: The IRS releases Notice 2014-21,37 which states that cryptocurrency is to be treated as property for federal U.S. income tax purposes. This is the first guidance ever released by the IRS on how to treat cryptocurrency.

November 6, 2014: According to the indictment, Ver files an amended 1040X (Individual Income Tax Return) and claims a deduction for the bitcoin donation on November 30, 2013.

2015

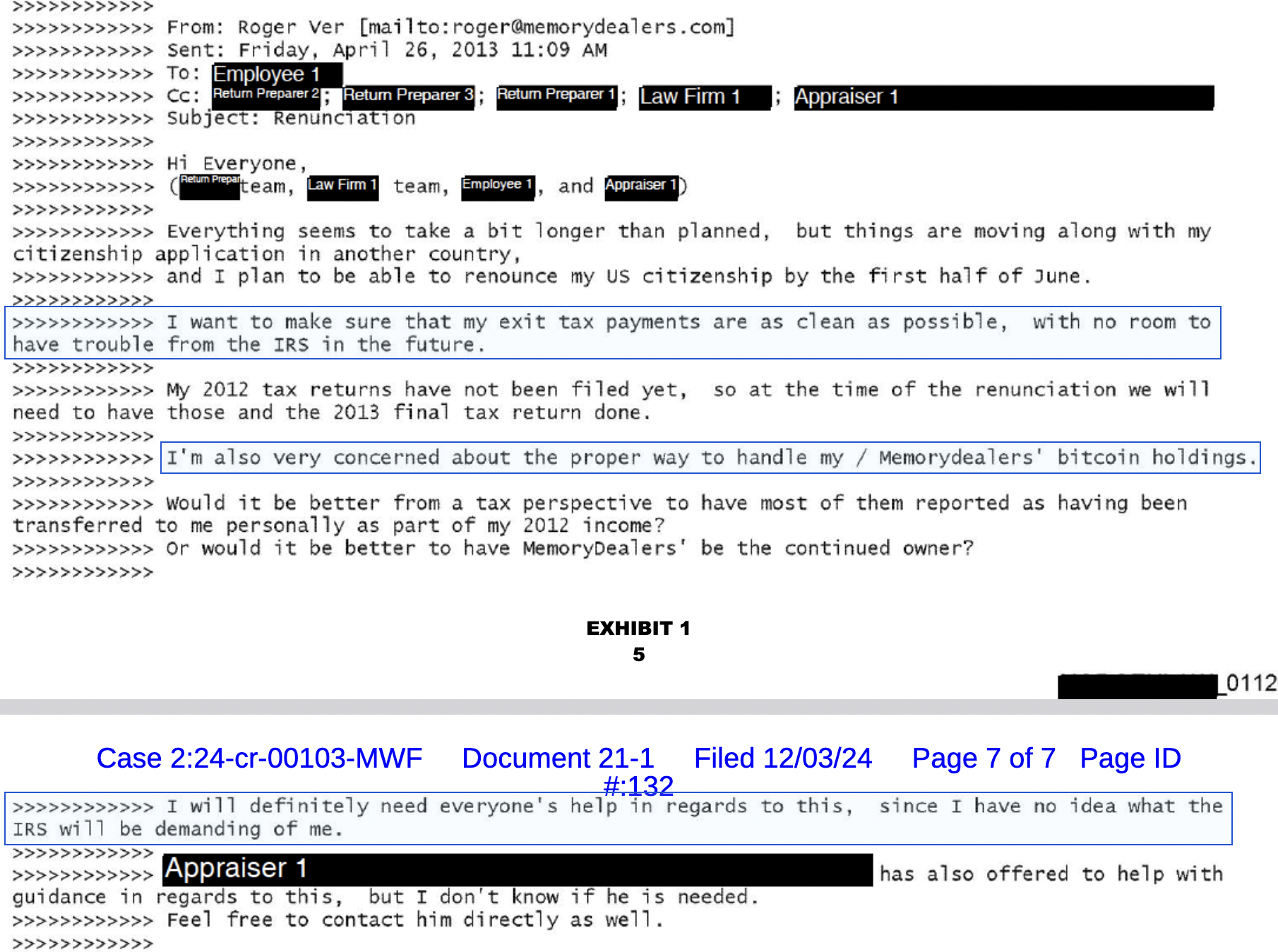

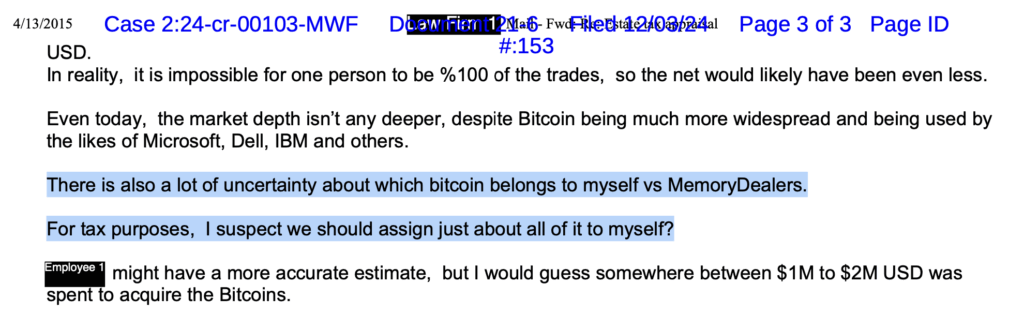

April 11-13, 2015: Exhibit 6 is an email exchange between Ver, Return Preparer 1, and Employee 1, in which Ver addresses the difficulties with estimating the tax liabilities of his bitcoin and other assets for his exit tax calculation.38 Ver notes the limited liquidity of the bitcoin markets, indicating that liquidating his bitcoins would not accurately reflect its value. Additionally, Ver shares his concern for distinguishing his personal bitcoins from those owned by his company.

In an email from Ver to Return Preparer 1, Ver writes, in part:

“There is also a lot of uncertainty about which bitcoin belongs to myself vs MemoryDealers. For tax purposes, I suspect we should assign just about all of it to myself?”

In the motion to dismiss, the defense cites the above email as evidence that Ver offered to take the more personally expensive approach and assign all of the bitcoin to himself, which would require the payment of both transfer and exit taxes. However, it was Ver’s counsel at the time who later suggested that Ver allocate the bitcoin among his companies and do corporate appraisals.

Note: Regarding the technical aspect of the custody of the bitcoin holdings, the motion to dismiss states, “all of the BTC were maintained in a group of wallets without a coin-by-coin designation of ownership, basis, or other data that might be kept for a capital asset (as opposed to a currency). Ver repeatedly informed his advisors that he could not unscramble the egg to figure out which BTC ‘belonged’ to which entity, as opposed to the amount of money used to acquire BTC for or through a given company.”

June 2015: According to the indictment, Ver obtains Appraiser 2 to value his companies for the exit tax calculation.

August 3-6, 2015: Exhibit 7 is an email exchange between Ver, Lawyer 1, and Return Preparer 1, in which they discuss the valuation of Ver’s bitcoin holdings for the exit tax.39 Ver addresses the complexities of determining the fair market value of his bitcoin holdings due to the volume of bitcoin he holds and the thin market at the time. Ver and his team also discuss the potential methods for estimating the fair market value of his bitcoin. The emails show Ver and his team addressing very difficult questions at a time when there was little guidance on how to treat cryptocurrency for tax purposes.

August 4, 2015: According to the indictment, for purposes of the exit tax, Appraiser 2 sends draft valuations of MemoryDealers and Agilestar to Employee 1, a MemoryDealers’ employee. MemoryDealers is valued at $2.25 million, which includes bitcoin valued at $1.3 million. Agilestar is valued at $4.3 million, which includes bitcoin valued at $113,582. Employee 1 then forwards the draft valuations to Return Preparer 2 (an outside Return Preparer for MemoryDealers and Agilestar). Return Preparer 2 inquires about the valuations of the companies’ bitcoin, stating the value should be “total Bitcoins x Average Market Price on Date of Valuation (2/3/14). If the value shown is that value, no problem; otherwise, an adjustment should be made, up or down, to show [Fair Market Value] of Bitcoins on that date.” Return Preparer 2’s response is forwarded to Ver by Employee 1 (follow-up on August 13).

August 12, 2015: Exhibit 3 is an email exchange between Ver, Lawyer 1, and Return Preparer 1, in which Ver and his team discuss the bitcoin valuation and company appraisals for the exit tax.40 Ver’s advisors outline the tax obligations using the fair market value of bitcoin despite the thin market. (This email exchange continues in Exhibits 4 and 5.)

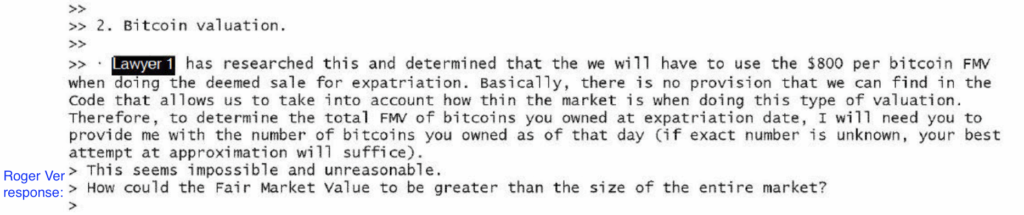

Below is a portion of an email exchange between Ver and Return Preparer 1.

“Bitcoin Valuation—Lawyer 1 [redacted] has researched this and determined that the [sic] we will have to use the $800 per bitcoin FMV when doing the deemed sale for expatriation. Basically, there is no provision that we can find in the Code that allows us to take into account how thin the market is when doing this type of valuation. Therefore, to determine the total FMV of bitcoins you owned at expatriation date, I will need you to provide me with the number of bitcoins you owned as of that day (if exact number is unknown, your best attempt at approximation will suffice).”

Roger Ver inline response:

“This seems impossible and unreasonable. How could the Fair Market Value to [sic] be greater than the size of the entire market?”

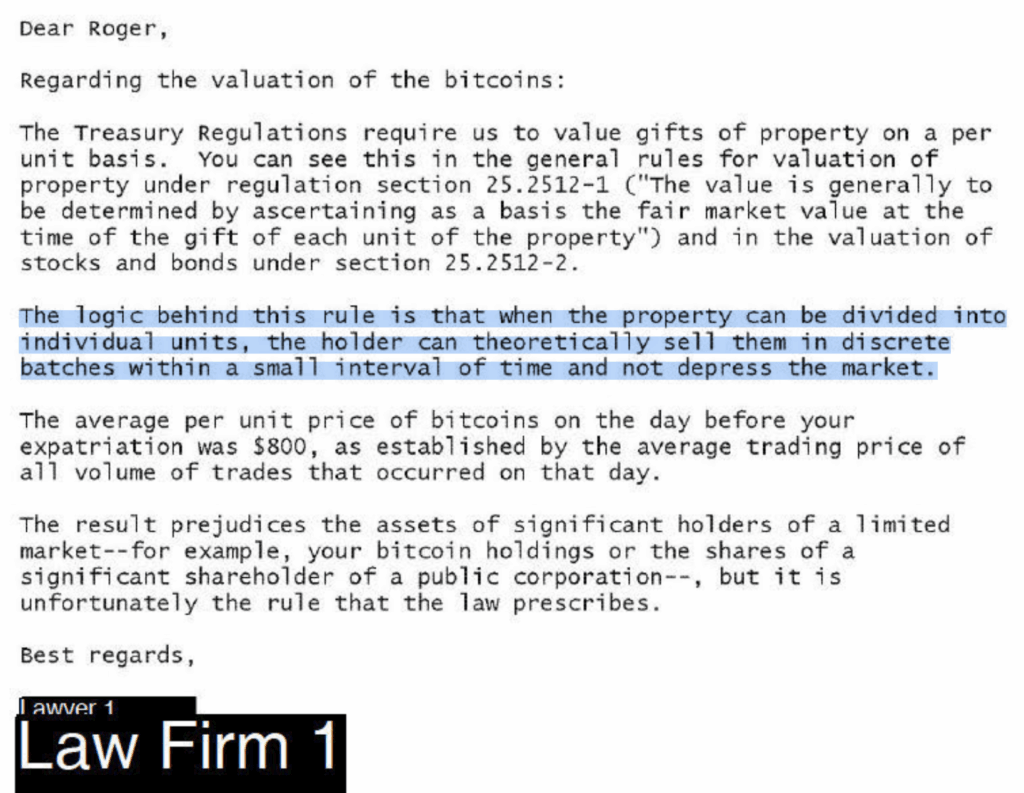

In a follow-up email sent on the same day, Lawyer 1 responds to Ver and Return Preparer 1:

“Dear Roger… Regarding the valuation… The logic behind this rule is that when the property can be divided into individual units, the holder can theoretically sell them in discrete batches within a small interval of time and not depress the market.”

The indictment portrays this correspondence as Lawyer 1’s final advice to Ver on how to value the bitcoin, but it is not. Following this exchange, Lawyer 1 conducts more research and comes to a different conclusion on how to conduct the valuation, but that is omitted from the indictment. (This discrepancy will be addressed in greater detail, see October 13-14, 2015.)

August 13, 2015: According to the indictment, Employee 1 confirms with Appraiser 2 that the previously provided draft valuations of MemoryDealers and Agilestar (sent on August 4) are the final versions (with no adjustments). Employee 1 then forwards the valuations to Law Firm 1 to include in Ver’s expatriation-related tax returns.

Note: Ver is being prosecuted for not rejecting Appraiser 2’s valuations of the companies. The U.S. government claims Ver should have known the valuations were significantly lower than each should have been despite his attorneys and other advisors not objecting to Appraiser 2’s valuations.

August 20 – November 17, 2015: Exhibit 8 is an email exchange between Ver and Appraiser 2, in which they discuss methods for determining the value of Ver’s bitcoin holdings (not accounted for in the company appraisals) for the exit tax.41 They address the difficulties given the thin bitcoin market at the time and the significance of Ver’s bitcoin holdings. (The conversation continues in Exhibits 9 and 10.)

October 13-14, 2015: Exhibit 4 (continued from Exhibit 3) is an email exchange between Ver, Return Preparer 1, and Lawyer 1, in which they continue to discuss the challenges of valuing Ver’s bitcoin holdings.42 Ver’s team suggests the need for third-party appraisals. (This exchange continues to Exhibit 5.)

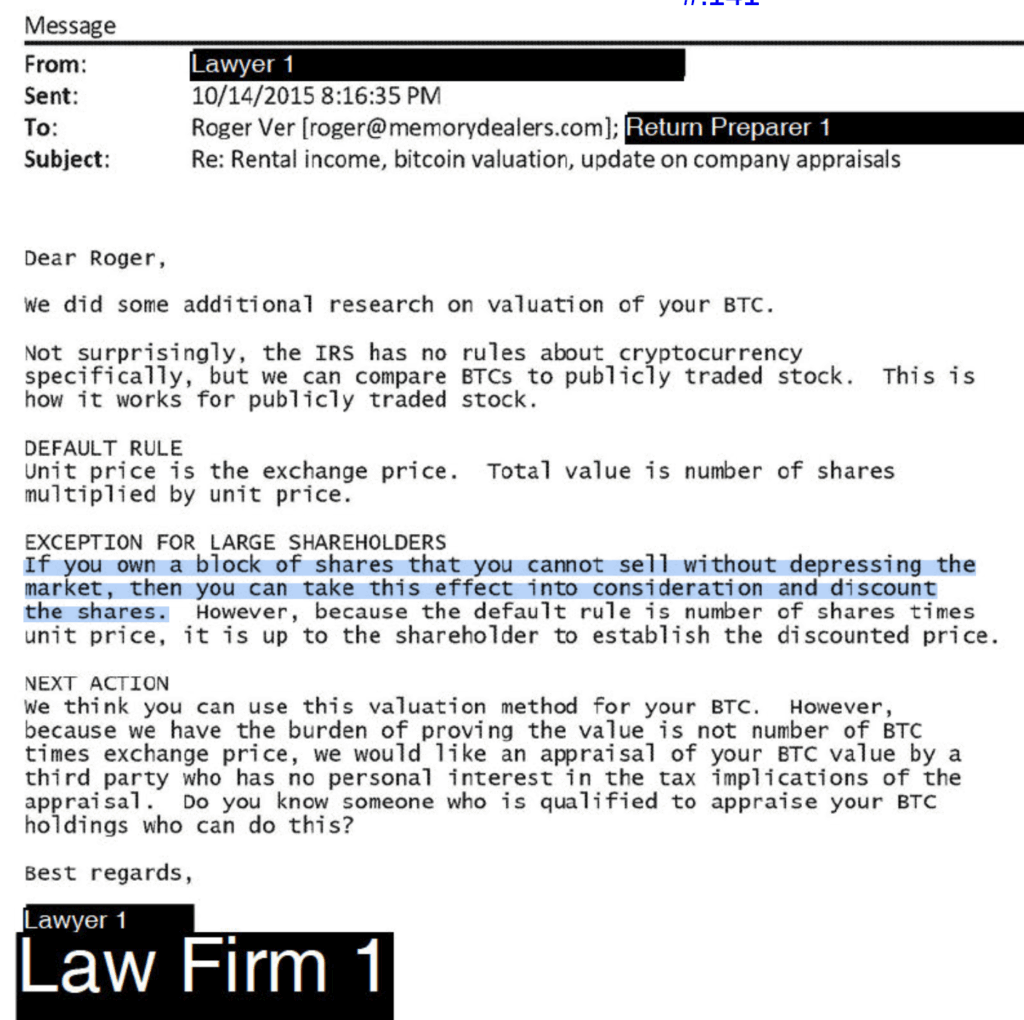

The email from Lawyer 1 sent to Ver on October 14, 2015, is particularly notable.

“Dear Roger,

We did some additional research on valuation of your BTC.

Not surprisingly, the IRS has no rules about cryptocurrency specifically, but we can compare BTCs to publicly traded stock. This is how it works for publicly traded stock.

DEFAULT RULE

Unit price is the exchange price. Total value is number of shares multiplied by unit price.

EXCEPTION FOR LARGE SHAREHOLDERS

If you own a block of shares that you cannot sell without depressing the market, then you can take this effect into consideration and discount the shares. However, because the default rule is number of shares times unit price, it is up to the shareholder to establish the discounted price.

NEXT ACTION

We think you can use this valuation method for your BTC. However, because we have the burden of proving the value is not number of BTC times exchange price, we would like an appraisal of your BTC value by a third party who has no personal interest in the tax implications of the appraisal. Do you know someone who is qualified to appraise your BTC holdings who can do this?

Best regards,

Lawyer 1 [name redacted]

Law Firm 1 [name redacted]”

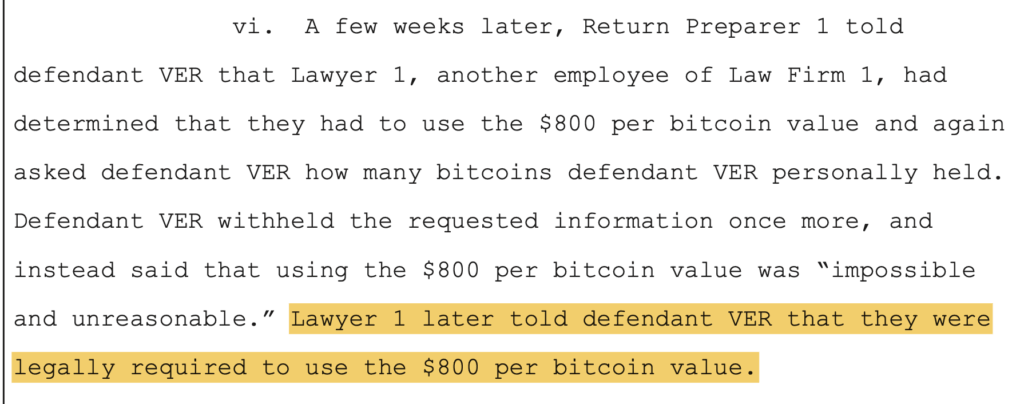

Lawyer 1 states that after doing additional research, Ver does not have to use the spot price method (total bitcoins x average market price on date of valuation) for the valuation of his bitcoin holdings if he cannot sell it without depressing the market. As mentioned previously, the contents of the above email are omitted from the indictment. The indictment only includes the prior advice given to Ver by Lawyer 1 (on August 12) as if it were Lawyer 1’s final advice. A selection from the indictment, pg. 11:

“vi. A few weeks later, Return Preparer 1 told defendant VER that Lawyer 1, another employee of Law Firm 1, had determined that they had to use the $800 per bitcoin value and again asked defendant VER how many bitcoins defendant VER personally held. Defendant VER withheld the requested information once more, and instead said that using the $800 per bitcoin value was ‘impossible and unreasonable.’ Lawyer 1 later told defendant VER that they were legally required to use the $800 per bitcoin value.”

A selection from the indictment, pg. 11

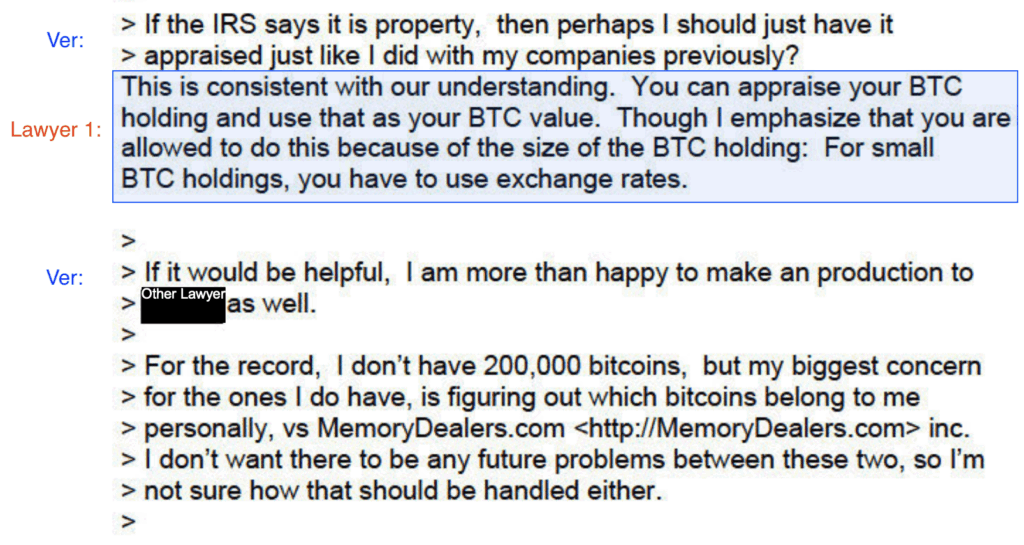

October 15, 2015: Exhibit 5 (continued from Exhibits 3 and 4) includes one additional email exchange (with inline responses) between Lawyer 1 and Ver, in which Lawyer 1 reiterates Ver does not have to use the spot price method of $800 per bitcoin for the valuation for the exit tax.43 (Again, this is omitted from the indictment, see above.)

Ver: “If the IRS says it is property, then perhaps I should just have it appraised just like I did with my companies previously?

Lawyer 1: This is consistent with our understanding. You can appraise your BTC holding and use that as your BTC value. Though I emphasize that you are allowed to do this because of the size of the BTC holding: For small BTC holdings, you have to use exchange rates….

Ver: …but my biggest concern for the ones I do have, is figuring out which bitcoins belong to me personally, vs MemoryDealers.com”

In summary, based on the emails from October 14-15, 2015, Ver is advised by Lawyer 1 that he could seek an appraisal that favors a more accurate simulation of what his bitcoin holdings would be worth on an open market (instead of the spot price method). Ver, once again, raises concerns on the difficulty of differentiating personal bitcoin from company-owned bitcoin.

October 26, 2015 (from Exhibit 8): Following his lawyer’s advice, Ver writes an email to Appraiser 2 and asks for an appraisal “for an amount of Bitcoins as of Feb. 4, 2014, in an illiquid market.” This is bitcoin not accounted for in the appraisals of MemoryDealers and Agilestar.

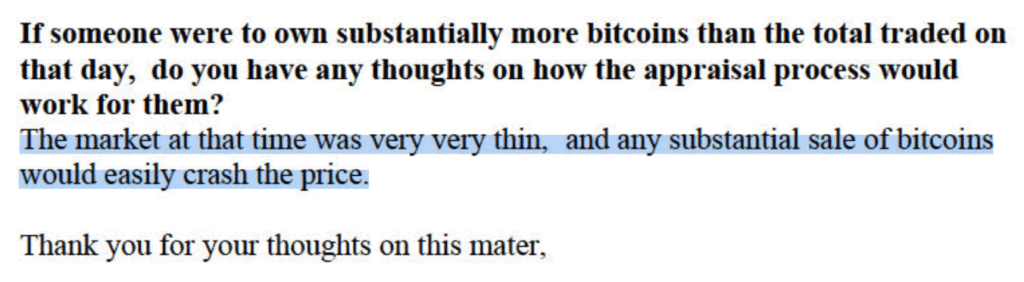

November 11-17, 2015 (from Exhibit 8): Ver and Appraiser 2 continue to discuss via email how to value the bitcoin in question for his exit tax. Ver emphasizes, “The market at that time was very very thin, and any substantial sale of bitcoins would easily crash the price.” Appraiser 2 states the valuation would depend in part on “trading volume volatility.”

In the indictment, the U.S. government claims Ver avoided questions from Appraiser 2 regarding the number of bitcoins he owned by focusing on the state of the bitcoin market. The defense argues Ver and his advisors were struggling with difficult questions given the lack of regulation surrounding cryptocurrency at the time. See the full email exchange from Exhibit 8 here.41

November 20 – December 6, 2015: Exhibit 9 (continued from Exhibit 8) is an email exchange between Ver, Lawyer 1, and Appraiser 2, in which Ver and his advisors discuss the ownership of the bitcoin in question (not included in the valuation of MemoryDealers and Agilestar) and its valuation for the exit tax.44 Ver and his advisors address the difficulties in distinguishing Ver’s personal bitcoin holdings from bitcoin held by his companies or that he held on behalf of others. Ver’s advisors suggest allocating bitcoin wallets based on associated accounts and transactions. (The conversation continues in Exhibit 10.)

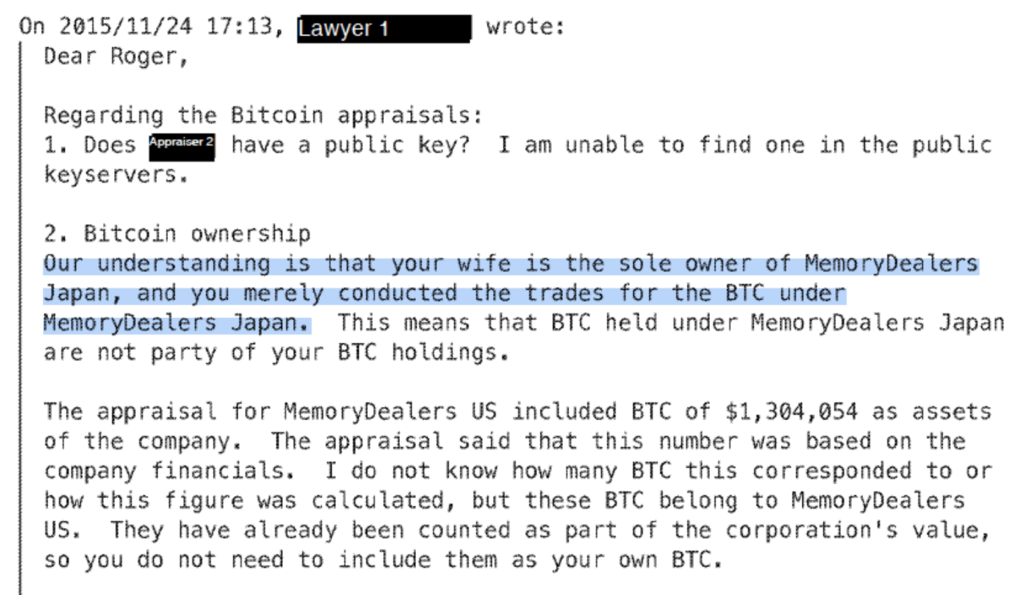

November 24, 2015 (from Exhibit 9): Lawyer 1 writes an email to Ver in which he shares the legal team’s understanding of the ownership of the bitcoins in question:

“2. Bitcoin ownership

Our understanding is that your wife is the sole owner of MemoryDealers Japan, and you merely conducted the trades for the BTC under MemoryDealers Japan. This means that BTC held under MemoryDealers Japan are not party [sic] of your BTC holdings.

The appraisal for MemoryDealers US included BTC of $1,304,054 as assets of the company. The appraisal said that this number was based on the company financials. I do not know how many BTC this corresponded to or how this figure was calculated, but these BTC belong to MemoryDealers US. They have already been counted as part of the corporation’s value, so you do not need to include them as your own BTC.”

In subsequent emails between November 24 and December 4, 2015, Lawyer 1 asks Ver how many bitcoins he owned personally. Ver states he gave his best estimate to Appraiser 2. The amount was 25,000 bitcoin.

December 5-6, 2015 (from Exhibit 9): Ver and Lawyer 1 continue to discuss the bitcoin in question (25,000) and the difficulty in determining the ownership of certain bitcoin wallets.

In one email, Ver writes in part, “25,000 is just a ballpark guess of how many bitcoins I had in my many different bitcoin wallets on Feb 4th 2014.” Ver then discusses how bitcoin wallets are owned.

In the final email in Exhibit 9, sent on December 6, 2015, Ver states that the 25,000 bitcoin estimate is bitcoin he held personally and does not include any amount he may be holding for others.

2016

January 8-13, 2016: Exhibit 11 is an email exchange between Ver, Lawyer 1, and Return Preparer 1, in which they discuss strategies for accurately reporting the bitcoin holdings for the exit tax.45 They consider if the bitcoin in question should be treated as personal property or property of MemoryDealers Japan. Ver considers the possibility of reporting the bitcoin as a gift to his partner (not legally married wife) in Japan.

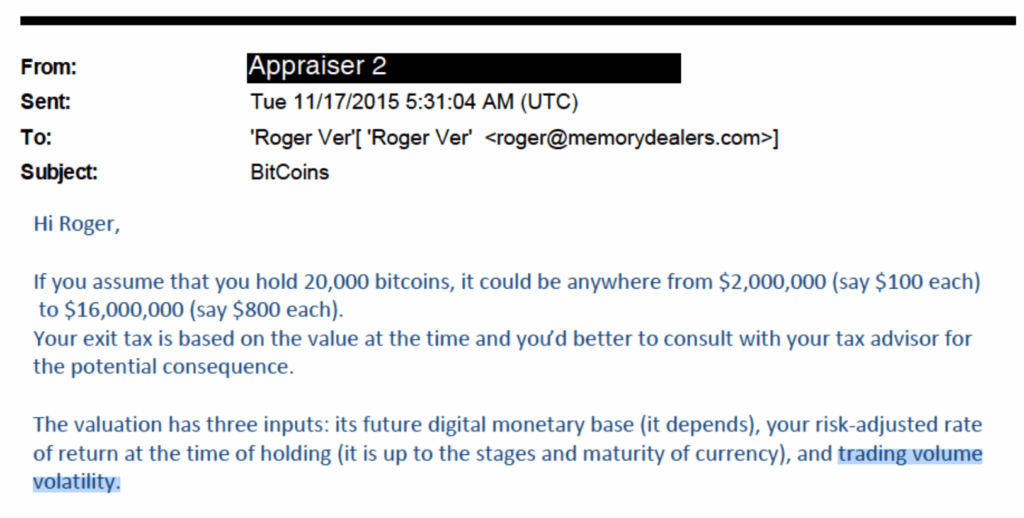

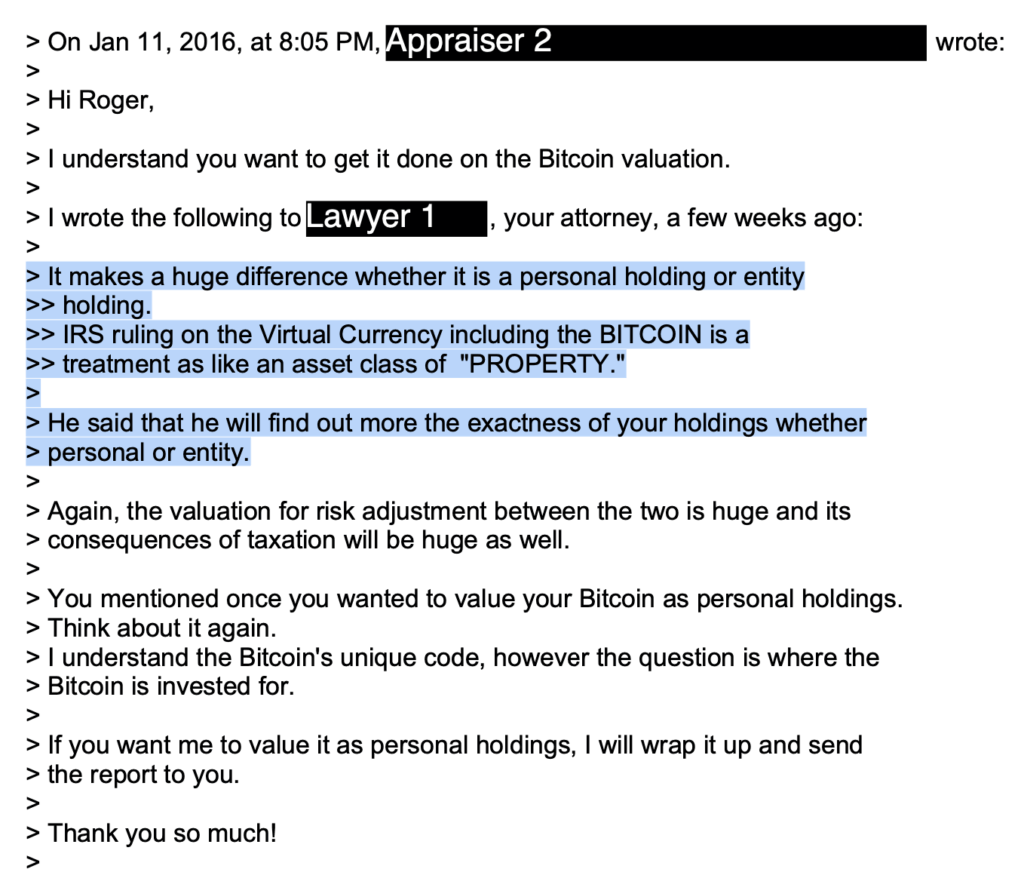

January 11, 2016: Exhibit 10 is a continuation from the email conversation between Ver and his advisors from Exhibits 8 and 9.46 Appraiser 2 responds to an earlier email from Ver asking for an update on the Bitcoin valuation.

“Hi Roger,

I understand you want to get it done on the Bitcoin valuation.

I wrote the following to Lawyer 1 [name redacted], your attorney, a few weeks ago:

It makes a huge difference whether it is a personal holding or entity holding. IRS ruling on the Virtual Currency including the BITCOIN is a treatment as like an asset class of ‘PROPERTY.’

He said that he will find out more the exactness of your holdings whether personal or entity.

Again, the valuation for risk adjustment between the two is huge and its consequences of taxation will be huge as well.

You mentioned once you wanted to value your Bitcoin as personal holdings. Think about it again. I understand the Bitcoin’s unique code, however the question is where the Bitcoin is invested for.

If you want me to value it as personal holdings, I will wrap it up and send the report to you.

Thank you so much!

Appraiser 2 [name redacted]”

In the email above, Appraiser 2 notifies Ver that it makes a significant difference for tax purposes if the bitcoin in question are personal or entity-owned. Appraiser 2 informs Ver that Lawyer 1 will verify the “exactness” of the bitcoin in question. Appraiser 2 conveys the importance of determining the “exactness” of the bitcoin holdings as opposed to Ver’s approach, which is the more personally expensive approach, of assigning all of it as personal property due to the significant tax implications that follow.

Note: According to the motion to dismiss, and as evidenced in the email from January 11, 2016, “Ver’s lawyers contemplated the potential entity ownership of Ver’s BTC before consulting with Ver regarding that potential approach.”

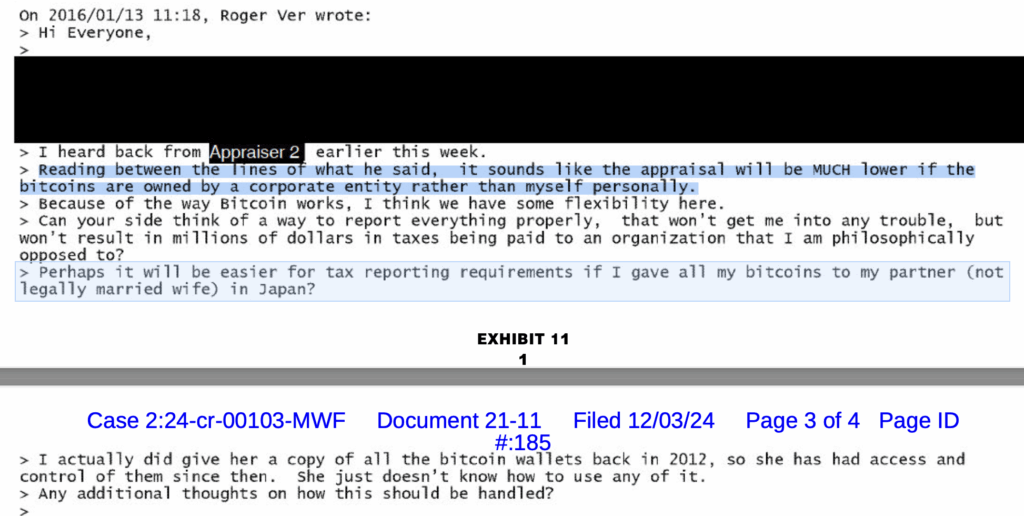

January 13, 2016 (from Exhibit 11): After learning of his counsel’s understanding of the ownership of the bitcoin in question as well as the tax implications of personally-owned bitcoin (see above), Ver emails Lawyer 1 and his other advisors, explaining what Appraiser 2 told him and shares additional options.

“Hi everyone,

[A paragraph is redacted]

I heard back from Appraiser 2 [redacted] earlier this week.

Reading between the lines of what he said, it sounds like the appraisal will be MUCH lower if the bitcoins are owned by a corporate entity rather than myself personally.

Because of the way Bitcoin works, I think we have some flexibility here.

Can your side think of a way to report everything properly, that won’t get me into any trouble, but won’t result in millions of dollars in taxes being paid to an organization that I am philosophically opposed to?

Perhaps it will be easier for tax reporting requirements if I gave all my bitcoins to my partner (not legally married wife) in Japan?

I actually did give her a copy of all the bitcoin wallets back in 2012, so she has had access and control of them since then. She just doesn’t know how to use any of it.

Any additional thoughts on how this should be handled?

[A paragraph is redacted]

Roger Ver”

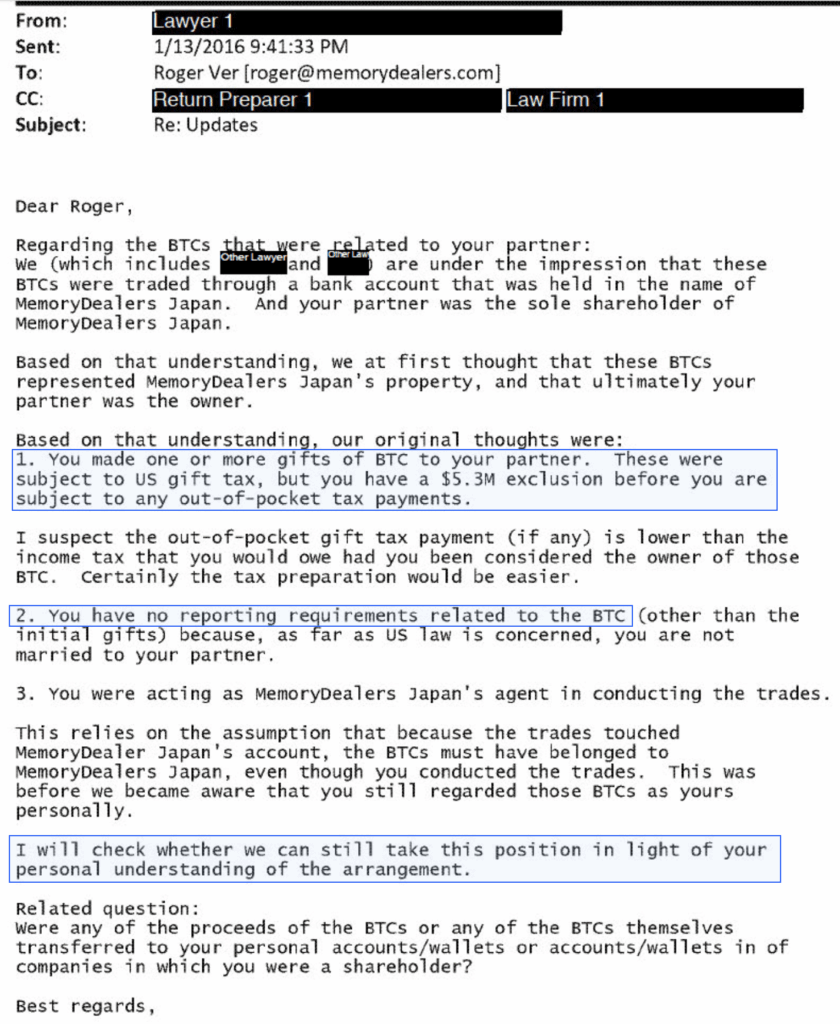

On the same day, Lawyer 1 responds to Ver’s email:

“Dear Roger,

Regarding the BTCs that were related to your partner:

We (which includes Other Lawyer [redacted] and Other Law Firm [redacted]) are under the impression that these BTCs were traded through a bank account that was held in the name of MemoryDealers Japan. And your partner was the sole shareholder of MemoryDealers Japan.

Based on that understanding, we at first thought that these BTCs represented MemoryDealers Japan’s property, and that ultimately your partner was the owner.

Based on that understanding, our original thoughts were:

1. You made one or more gifts of BTC to your partner. These were subject to US gift tax, but you have a $5.3M exclusion before you are subject to any out-of-pocket tax payments.

I suspect the out-of-pocket gift tax payment (if any) is lower than the income tax that you would owe had you been considered the owner of those BTC. Certainly the tax preparation would be easier.

2. You have no reporting requirements related to the BTC (other than the initial gifts) because, as far as US law is concerned, you are not married to your partner.

3. You were acting as MemoryDealers Japan’s agent in conducting the trades.

This relies on the assumption that because the trades touched MemoryDealer Japan’s account, the BTCs must have belonged to MemoryDealers Japan, even though you conducted the trades. This was before we became aware that you still regarded those BTCs as yours personally.

I will check whether we can still take this position in light of your personal understanding of the arrangement.

Related question:

Were any of the proceeds of the BTCs or any of the BTCs themselves transferred to your personal accounts/wallets or accounts/wallets in [sic] of companies in which you were a shareholder?

Best regards,

Lawyer 1 [name redacted]

Law Firm 1 [name redacted]”

The email above shows that Ver’s advisors were under the impression that the 25,000 bitcoin in question, that Ver originally thought were his personally, were traded through a bank account that was held in the name of MemoryDealers Japan. Thus, Lawyer 1 and the other advisors considered that at some point Ver made one or more gifts of bitcoin to his partner (the sole shareholder of MemoryDealers Japan). When conducting subsequent trades, Ver was acting as an agent of MemoryDealers Japan.

Ver’s advisors indicate that if this is the case, Ver has no reporting requirements related to the bitcoin in question with the exception of the initial gifts. In other words, the bitcoin in question are not subject to U.S. federal income tax or the exit tax as it is considered property of MemoryDealers Japan for which Ver’s (not legally married) partner is the sole shareholder.

Lawyer 1 then goes on to state that they will check if they can still take this position given Ver’s previous understanding that he personally owned the 25,000 bitcoin in question.

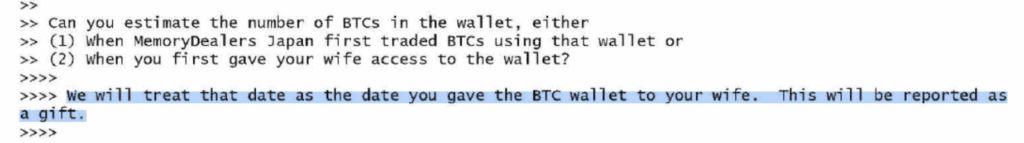

February 12, 2016: Exhibit 12 is an email exchange between Ver, Lawyer 1, and Return Preparer 1 in which they follow up on the bitcoin in question and decide to treat transfers of the bitcoin wallet as a taxable gift.47 They address challenges such as reconstructing historical records for bitcoin transactions, including those for personal expenses and those involving MemoryDealers Japan.

An email between Lawyer 1 and Ver reads in part:

“Can you estimate the number of BTCs in the wallet, either

(1) when MemoryDealers Japan first traded BTCs using that wallet or

(2) When you first gave your wife access to the wallet?

We will treat that date as the date you gave the BTC wallet to your wife. This will be reported as a gift.”

The text highlighted in blue is from Lawyer 1.

According to the motion to dismiss, the above email, in addition to the email from Lawyer 1 on January 13, 2016, shows that it was Ver’s lawyers who determined Ver ought to treat the bitcoin in question as property of MemoryDealers Japan. According to Ver’s counsel at the time, Ver’s “provision of the wallet’s passcode and use of MemoryDealers Japan’s account to trade constituted a gift of the resulting BTC to the owner of MemoryDealers Japan.” Ver’s then-counsel understood that while the funds originated from Ver, he made one or more gifts to his partner (subject to U.S. gift tax), and thus any subsequent trades were done by Ver as an agent of MemoryDealers Japan. To reiterate, this made the bitcoin in question only subject to U.S. gift tax, not the exit tax or U.S. federal income tax, according to Ver’s counsel at the time.

Ver, then taking his counsel’s advice, treats the 25,000 bitcoin as a gift subject to U.S. gift tax and files a Form 709.34 The U.S. government claims the form was false. However, the U.S. government also omits from the indictment the communications between Ver and his advisors from January 13 and February 12, 2016.

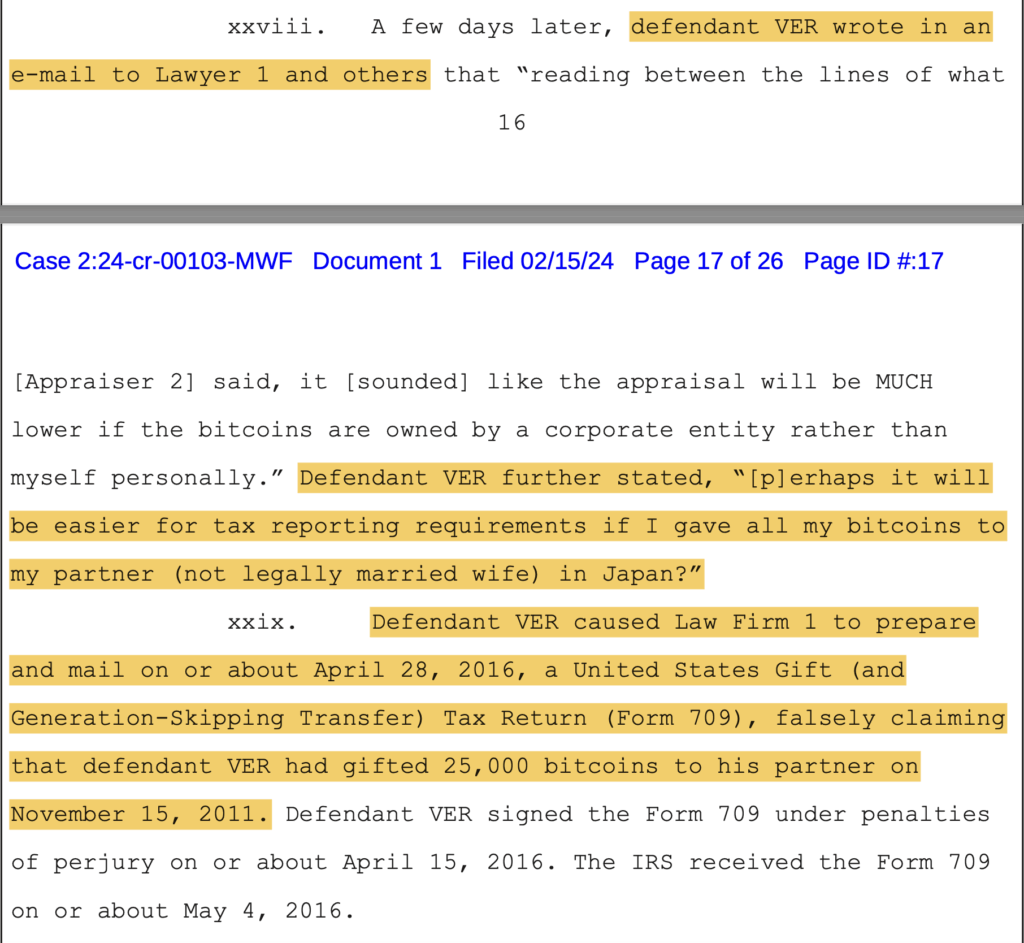

“xxviii. A few days later, defendant VER wrote in an e-mail to Lawyer 1 and others that ‘reading between the lines of what [Appraiser 2] said, it [sounded] like the appraisal will be MUCH lower if the bitcoins are owned by a corporate entity rather than myself personally.” Defendant VER further stated, “[p]erhaps it will be easier for tax reporting requirements if I gave all my bitcoins to my partner (not legally married wife) in Japan?”

xxix. Defendant VER caused Law Firm 1 to prepare and mail on or about April 28, 2016, a United States Gift (and Generation-Skipping Transfer) Tax Return (Form 709), falsely claiming that defendant VER had gifted 25,000 bitcoins to his partner on November 15, 2011. Defendant VER signed the Form 709 under penalties of perjury on or about April 15, 2016. The IRS received the Form 709 on or about May 4, 2016.”

A selection from the indictment, pages 16-17

Instead, the indictment selectively quotes from Ver’s January 13, 2016, email and then jumps to Ver’s filing of Form 709 in April 2016, thus portraying a situation in which Ver acted on his own and did not act upon the advice of his counsel.

February 2016: The U.S. government’s opposition to the motion to dismiss cites a speech given by Ver at this time at an annual convention, “Anarchapulco.” According to the U.S. government’s document, Ver stated the following during his speech: “Bitcoin completely undermines the power of every single government…to tax people’s income, to control them in any way…. Bitcoin [ ] makes it so incredibly easy for people to hide their income or evade taxes….”

March 17, 2016: According to the indictment, Ver learns from Return Preparer 3, another one of MemoryDealers’ and Agilestar’s outside return preparers, that when he expatriated, MemoryDealers and Agilestar became C-Corporations and thus all of MemoryDealers’ and Agilestar’s assets “rolled into” them.

April 15, 2016: Ver signs Form 709, a U.S. gift tax return, which indicates he had gifted 25,000 bitcoin to his partner on November 15, 2011.

The U.S. government argues the form “falsely claimed that Ver had gifted 25,000 bitcoins to his partner on November 15, 2011.” The defense argues Ver was advised by his then-counsel to treat the 25,000 bitcoin as a taxable gift.

April 15, 2016: Ver signs Form 8854 (Initial and Annual Expatriation Statement).

The U.S. government claims the form failed to report personally owned bitcoin, falsely reported Ver’s net worth, and underreported the fair market values of MemoryDealers and Agilestar.

The defense argues in the motion to dismiss that Ver’s accountants provided Appraiser 2 with all the records needed to prepare valuations (including information on the bitcoin owned by the companies). The document states, “Appraiser 2 rejected any valuation of Ver’s companies based on the spot price of their assets and instead appraised them using a complex analysis that he explained in a lengthy report.” Ver’s defense argues this was very reasonable given the lack of statutory clarity, at the time, on how to treat cryptocurrency. Additionally, “none of the lawyers who reviewed the [Appraiser 2’s] report objected or warned Ver that the valuation was too low.”

With regard to the “personally-owned” bitcoin, Ver was instructed by his then-counsel to treat it as property of MemoryDealers Japan subject to U.S. gift tax but not the exit tax or U.S. income tax.

April 15, 2016: Ver signs the 2014 Form 1040NR (non-resident alien income tax return).

The U.S. government claims the form failed to report any gain from the constructive sale of personally owned bitcoin and underreported gains from the constructive sales of MemoryDealers and Agilestar. Ver is also accused of falsely reporting the total capital gains and amount owed on this form.

According to the defense, the gains from the “personally owned” bitcoin were not listed on the 2014 Form 1040NR because Ver’s lawyers advised him that this bitcoin was not personal property but rather property of MemoryDealers Japan, which was not subject to U.S. income tax or exit tax. Furthermore, the gains from the constructive sales of MemoryDealers and Agilestar were based on a valuation done by Appraiser 2, which was approved by Ver’s then-counsel (see above entry).

April 28, 2016: Law Firm 1 prepares and mails Form 709 to the IRS.

May 4, 2016: The IRS receives Form 709.

May 4, 2016: Law Firm 1 prepares and mails Ver’s 2014 Forms 1040NR and 8854 to the IRS in Charlotte, NC.

May 10, 2016: The IRS receives the 2014 Forms 1040NR and 8854.

July 11 – August 7, 2016: Exhibit 13 is an email exchange between Ver and Return Preparer 1, in which they discuss the potential sale of MemoryDealers and Agilestar and the related tax implications and reporting requirements.48Additionally, the two address capital gains exemptions for non-residents. Return Preparer 1 follows up with Ver on the status of the previously filed 2014 forms 8854 and 1040NR.

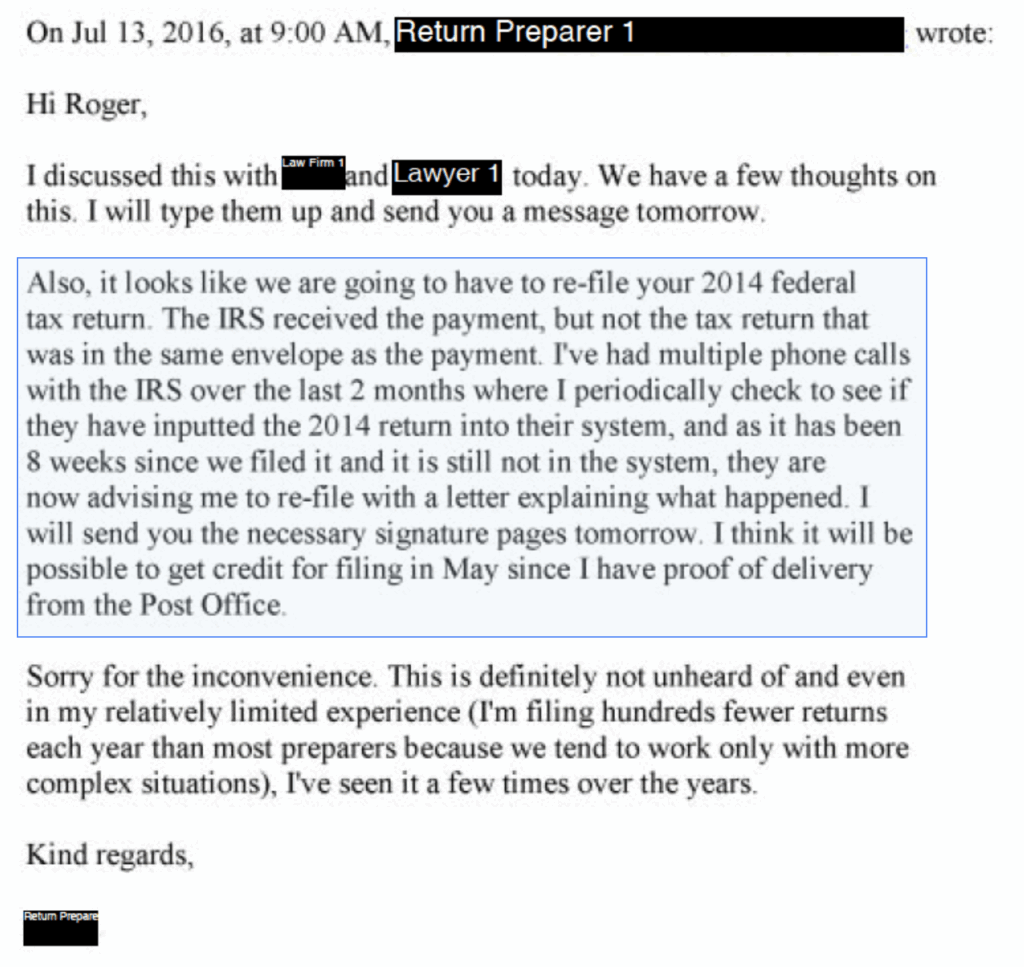

July 13, 2016 (from Exhibit 13): Return Preparer 1 notifies Ver that they must refile Ver’s 2014 forms 8854 and 1040NR.

“The IRS received the payment, but not the tax return that was in the same envelope as the payment…. [T]hey are now advising me to refile with a letter explaining what happened.”

The indictment claims Return Preparer 1 was erroneously informed that the IRS did not receive forms 8854 and 1040NR mailed on May 4, 2016.

July 14, 2016: Ver re-signs the 2014 Forms 1040NR and 8854.

July 19, 2016: Law Firm 1 mails the re-signed Forms 1040NR and 8854 to the IRS Department of Treasury in Austin, TX.

Note: Ver is charged for mailing the alleged false forms a second time. The above actions in July 2016 account for the second charge of mail fraud.

July 22, 2016: The IRS receives the re-signed 2014 Forms 1040NR and 8854.

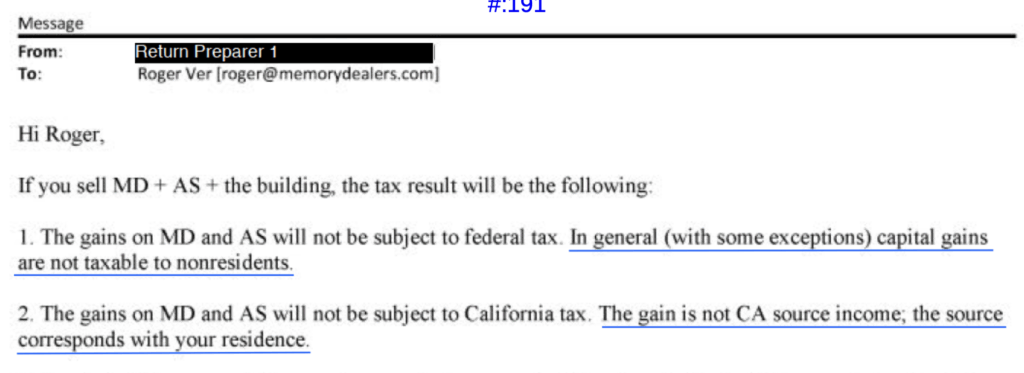

Around August 7, 2016 (from Exhibit 13): Return Preparer 1 responds to a previous inquiry from Ver concerning the selling of MemoryDealers and Agilestar and the associated real estate. Ver asks if he would owe an additional U.S. tax on such a sale. Return Preparer 1 responds, in part, with the following:

“Hi Roger,

If you sell MD + AS + the building, the tax result will be the following:

- The gains on MD and AS will not be subject to federal tax. In general (with some exceptions) capital gains are not taxable to nonresidents.*

- The gains on MD and AS will not be subject to California tax. The gain is not CA source income; the source corresponds with your residence.”

Thus, as shown above, the advice given to Ver by his advisor, Return Preparer 1, was that “capital gains are not taxable to nonresidents.” Therefore, the defense argues, Ver was of the understanding that the gains from the sale of MemoryDealers and Agilestar would not be subject to California tax because capital gains taxes correspond to the residence of the seller. By this time, Ver had already expatriated and was not a resident of the United States.

2017

While Ver is no longer a U.S. citizen or resident, he is still required to report to the IRS and pay taxes related to his U.S.-based companies, MemoryDealers and Agilestar. Ver continues to rely on an expert team of lawyers and tax advisors to help prepare his tax returns. Ver retains Law Firm 1 to help submit his 2017 Form 1040NR.

According to the indictment, by 2017, Ver had opened personal accounts on several cryptocurrency exchanges including Kraken, Bitfinex, Bittrex, and Poloniex. MemoryDealers continues to receive payments from customers in Bitcoin until September 2017.

February 13, 2017: According to the U.S. government’s opposition to the motion to dismiss, Jeremiah Haynie, one of the IRS special agents investigating Ver’s case, submits a declaration citing a video posted to YouTube on this date titled “Roger Ver at Anarchapulco 2016” on the channel “Anarchapulco.” Special Agent Haynie obtained and reviewed this video as evidence.