The GENIUS Act and Its Implications for Financial Transaction Freedom

By Tobi Maier, Esq.

On July 18, 2025, President Trump signed the so-called GENIUS (Guiding and Establishing National Innovation for U.S. Stablecoins) Act into law.1 This act creates a legal framework for so-called stablecoins. The implications of this legislation cannot be overstated.

I. What Are Stablecoins?

Stablecoins are a digital currency emitted by private parties, tied in value to a specific currency (or, theoretically, an asset or index). In the case of so-called payment stablecoins, which the GENIUS Act primarily addresses, the stablecoins are tied to the price of the U.S. dollar (USD). Hence, while other cryptocurrencies fluctuate in relation to the dollar, a payment stablecoin does not. This does not mean it won’t gain or lose purchasing power; it actually will, in exactly the same amount as the U.S. dollar. Payment stablecoins simply will retain the same valuation in USD and, as a result, the user won’t be subject to capital gains taxes (which are assessed based on an asset’s valuation in comparison to the U.S. dollar).

This article focuses solely on payment (i.e., dollar-denominated) stablecoins, as defined in § 2(22) of the GENIUS Act and regulated by the Act. Non-payment stablecoins (see § 14 of the GENIUS Act) could be tied to the value of any other commodity, security, currency, asset, or index, but under U.S. law, they would be subject to capital gains tax and are, therefore, legally impractical for payment purposes. Instead, non-payment stablecoins serve as an investment vehicle, similar to other securities and derivatives.

The main implications of stablecoins, in terms of freedom and daily life, are the potential for stablecoins to replace cash, coupled with the danger of stablecoin programmability. All types of stablecoins are programmable, but due to the tax implications, it is payment stablecoins that threaten to replace cash.

II. Advantages of Stablecoins

Demand for U.S. Treasury Bonds

Stablecoins need to be backed either by short-term Treasury bills, notes, or bonds (all of which must have a maturity date of 93 days or less), or by U.S. coins and currency. Consequently, the demand for U.S. Treasury bonds is likely to increase substantially. In light of the divestment from U.S. debt by major foreign traditional holders of such bonds, this will allow the U.S. government to refinance its debt by selling it to emitters of stablecoins, who, in turn, will have it financed by stablecoin users.

Fees

In theory, stablecoins should allow for international transfers of funds to be performed at relatively low cost. This was once the argument made in favor of cryptocurrencies as well. However, in the case of Bitcoin, for example, the exact opposite ended up happening: fees for transactions have skyrocketed. Whether international stablecoin transfers will end up being cheaper than other means of sending money across international borders remains to be seen. For everyday transactions, stablecoin use may end up being either cheaper or more expensive than the use of other electronic forms of payment (which tend to amount to several percent of each transaction, usually paid by the vendor) and definitely more expensive than cash, which is free to use.

No Capital Gains Tax

When compared to cryptocurrencies, stablecoins have the advantage that their valuation in USD (for U.S. dollar stablecoins) does not fluctuate and, therefore, does not subject its user to capital gains tax. Someone paying for a cup of coffee in Bitcoin would have to pay capital gains tax on the difference in the BTC-USD exchange rate between the time of obtaining that Bitcoin and the time of spending it. In practice, this is near impossible when used for everyday transactions, exposing the user to liability for tax evasion.

III. Dangers of Stablecoins

The dangers of stablecoins are essentially exactly the same as for central bank digital currencies (CBDCs). Specific dangers include surveillance, vulnerability to disruption (e.g., due to dependence on the Internet and electricity as well as hackability risks), and programmability. The combination of surveillance and programmability, in particular, poses perhaps the most existential threat to human freedom in history.

Surveillance

Any digital transaction is documented and recorded. Third parties can both lawfully and unlawfully obtain your entire digital transaction history and draw all kinds of conclusions. For example, they can create location and movement profiles, which can be used to predict when you are not home and can be robbed. Information on unhealthy habits can be used to increase your health insurance premiums or deny coverage. Transaction and purchase data can also inform conclusions about whether you hold political beliefs unpopular with those in power and whether you are “compliant” with certain policies, such as lockdowns. The accuracy of inferences that can be drawn with modern algorithms and computing power is beyond impressive.

Stablecoins will likely be issued on distributed ledgers, many of which are expected to be open or public. This will make accessing, aggregating, and applying transaction data much easier than is the case in the existing banking system.

Vulnerability to Disruption

Stablecoins, just like any electronic form of payment, require electricity, a stable and reliable Internet connection, and data center integrity. Power outages or any disruption in Internet connectivity or server maintenance render electronic payments impossible. Although such disruptions are usually temporary, they can pose serious problems when they are longer-lasting. At a minimum, if you don’t have cash and are dependent on a timely transaction (e.g., you need to purchase gas or a transportation ticket to get home or to an appointment), disruptions will cause serious inconvenience. Experience with natural disasters is causing an increasing number of countries to move away from all-digital payment systems and return to encouraging the use of physical cash.

A second consideration has to do with the fact that anything that is online is vulnerable to cyberattacks. Stablecoins are no exception. Unfortunately, once a hacker has access to your account, your loss can be total. Without cash, you won’t even be able to make simple daily transactions like getting gas or food.

Finally, if you forget your password or otherwise get locked out of your account (e.g., due to a computer glitch or human error), you won’t be able to use your stablecoins either.

Programmability

Programmability essentially means that stablecoins in your virtual wallet may not work for you even if they work for your neighbor for the identical transactions. The issuers of stablecoins can remotely and automatically block specific transactions or users and can freeze or seize individual users’ stablecoins. This feature of programmability, in combination with the complete surveillance of stablecoin transactions, allows for the implementation of a Chinese-style social credit score system, where unapproved behavior automatically leads to sanctions in the form of an individual’s inability to perform certain transactions.

These dangers are exactly why the opposition against CBDCs has grown rapidly in the last few years and why many states have passed legislation outlawing them. (Federal legislation to that effect has been introduced as well.) Ironically, stablecoins have the very same problems as CBDCs, including, most significantly, the threat they pose to human freedom. The main difference is that CBDCs are issued by a central bank (e.g., the Fed), whereas stablecoins are issued by private institutions other than a central bank. For the dangers listed above, this makes no difference whatsoever. Due to the nomenclature, however, many people erroneously associate stablecoins with cryptocurrencies rather than CBDCs.

IV. Effects of the GENIUS Act

Government Ability to Control Transactions

As § 3(h)(2) of the GENIUS Act shows, the Secretary of the Treasury has the authority “to block, restrict, or limit transactions involving payment stablecoins.” In fact, per § 4(a)(6), only stablecoins whose issuers have the technological capability to allow for the blocking of individual transactions or users may issue payment stablecoins.

While this, by itself, does not implement a social credit score system, it does legally ensure that payment stablecoins technologically allow for the implementation and activation of one.

Due to these requirements, stablecoins make it possible to take “Trudeauing” (i.e., the penalization of individuals for stepping out of line and expressing politically inconvenient opinions) to the next level. (The term was coined after former Canadian prime minister Justin Trudeau, without any due process, froze the bank accounts of Canadians who protested against his vaccination policies.) The Canadian prime minister was able to broadly freeze the bank accounts of those individuals he wanted to punish; however, completely freezing someone’s entire bank account is a radical move, certain to draw attention and legal backlash. Stablecoins allow for a much more nuanced application of pressure, with the denial of individual transactions facilitating a sliding scale of pain to nudge individuals away from actions not approved of by those in power.

Being able to monitor and control transactions does appear desirable from a law enforcement perspective, of course, for example, to fight crime and terrorism. However, the very same mechanisms can easily be applied for political, policy, or personal reasons. This is not possible with physical means of direct payment, such as cash, barter, gold, or silver.

The sections of the GENIUS Act on money-laundering (§§ 5, 8, and 9), which require monitoring of transactions as well as the ability to deny transactions remotely, must be viewed in that same light. Although the political and criminological desire to have these mechanisms in place is understandable (and is similar to what is, in a more basic form, already in place for banking and electronic payments), the potential for abuse, human error, and technical glitches is enormous. Bank accounts and credit cards already get frozen by accident, for example, when someone at a bank, the IRS, or another entity mistakenly puts in the wrong code or account number. In the case of stablecoins or CBDCs, such an error (or intentional decision) affects not just one of your cards or accounts but potentially your ability to pay for anything, anywhere, whatsoever.

No Privacy

Unlike a physical payment method, such as cash, any electronic means of transfer requires a database entry in order for the transaction to be possible. This inevitably means that the transaction and the persons transacting are being recorded. By default, there is no privacy.

As § 4 (a)(12)(B)(ii)(II) of the GENIUS Act shows, if a company “receives consent from the consumer,” non-public personal information obtained from stablecoin transactions may be used to target, personalize, and rank advertising and other content, as well as sold to third parties and shared with non-affiliates. A look at the current practice regarding terms and conditions, as well as license agreements, shows how this will likely look in practice: to use a stablecoin, the consumer will have to click on “I agree”—and that’s it, consent is obtained (hidden in a long document or scroll-text, full of legalese, which almost nobody will actually read). The only alternative will be not to use it, which, like not using credit cards, email, or even smartphones, will become more and more cumbersome and will simply leave the individual who chooses to opt out marginalized from much of society.

Voluntariness in Name Only

The GENIUS Act does not make the use of stablecoin mandatory, abolish cash, or even allow for permitted stablecoin issuers to market a payment stablecoin as legal tender (see § 4 (a)(9)). However, § 3 (g) implies that stablecoins issued by a permitted payment stablecoin issuer will be treated as cash.

Also, while § 4 (8)(A) does not allow a permitted payment stablecoin issuer to provide services to a customer on the condition that the customer obtain an additional paid product or service from the permitted payment stablecoin issuer, it does not prohibit the opposite: a provider of a service or product making the sale or service conditional upon the customer using stablecoin or a particular stablecoin.

§ 4 (a)(12)(B) prohibits “a public company that is not predominantly engaged in 1 or more financial activities, and its wholly or majority owned subsidiaries or affiliates [from issuing] a payment stablecoin unless the public company obtains a unanimous vote of the Stablecoin Certification Review Committee.” However:

- That prohibition can be circumvented with creative ownership structures where the public company not predominantly engaged in financial activities is not the direct majority owner.

- A company subject to this restriction can obtain the unanimous vote of the Stablecoin Certification Review Committee.

- Financial companies can own companies that emit stablecoins (or emit payment stablecoins themselves) and, at the same time, own or acquire companies engaged in other activities, such as providing goods and services.

Hence, there are several ways in which a company can be or become, at the same time, both a permitted payment stablecoin issuer and a provider of crucial goods or services, including a company holding a monopoly on certain markets, goods, or services.

Easing of Government Obligations

Per § 4 (e)(1), stablecoins are not backed by the FDIC. This will likely reduce the federal government’s exposure to liability in case of bank failures.

Instead, per § 4 (a)(1)(A)(iii), the issuer of a payment stablecoin is required to back the stablecoins on at least a one-to-one basis with reserves comprising either cash, deposits, certain securities, or Treasury bonds with a maturity date of 93 days or less. Conveniently for the federal government, this is almost certain to increase the demand for government debt at a time when major traditional holders of U.S. sovereign debt, such as China, are divesting themselves of it.

Prohibition on Individual Felons Only

Per § 4 (f), individuals convicted of certain financial crimes are ineligible to serve as an officer or director of a payment stablecoin issuer. What is noteworthy is that the wording does not include entities (or “persons,” which could include both). This is of particular significance, because five major banks have pled guilty to financial felonies (Citicorp, JPMorgan Chase, Barclays, the Royal Bank of Scotland, and UBS).2 Given that § 4 (f) only covers individuals, these institutions could serve as permitted payment stablecoin issuers, despite the fact that they would be ineligible to serve as an officer or director of one, were they individuals rather than corporations.

Relationship between Retail Customer and Federal Reserve Member Banks

The GENIUS Act does not create a direct relationship between end-customers using stablecoins and the Fed, and it explicitly states in § 4 (a)(13) that “Nothing in this Act shall be construed as expanding or contracting legal eligibility to receive services available from a Federal Reserve bank or to make deposits with a Federal Reserve bank, in each case pursuant to the Federal Reserve Act.”

This is probably the main difference between CBDCs and stablecoins. However, nothing prevents a direct relationship between a retail customer and a member and shareholder of the New York Fed or of one of the other 11 regional Federal Reserve banks, which can create subsidiaries to issue stablecoins.

No Interest

Payment stablecoin issuers are prohibited from paying the holders of stablecoins any form of interest or yield solely in connection with the holding, use, or retention of such payment stablecoins (§ 4(a)(11)).

Existing Stablecoins Not Grandfathered

All currently existing payment stablecoins (Tether, etc.) will have to comply with the GENIUS Act. In other words, there is no grandfather clause. The Act takes effect either 180 days after its enactment or 120 days after the date on which the primary Federal payment stablecoin regulators issue any final regulations implementing this Act, whichever comes first (§§ 20, 3(a), 4(e)(3)).

Anti-CBDC Act Window Dressing

In March 2025, the so-called Anti-CBDC Surveillance State Act (H.R. 1919) was introduced. It passed the House in July but has yet to pass the Senate.

This Act, assuming it ever passes the Senate and is signed into law by the President, only prohibits a Federal Reserve Bank from issuing a CBDC. It has no effect on the GENIUS Act and won’t affect, restrict, or prohibit stablecoins. Because stablecoins are issued by entities other than the Fed, they are outside the scope of the Anti-CBDC Surveillance State Act. Nevertheless, stablecoins have all the features that make CBDCs such a powerful surveillance state tool: programmability and trackability.

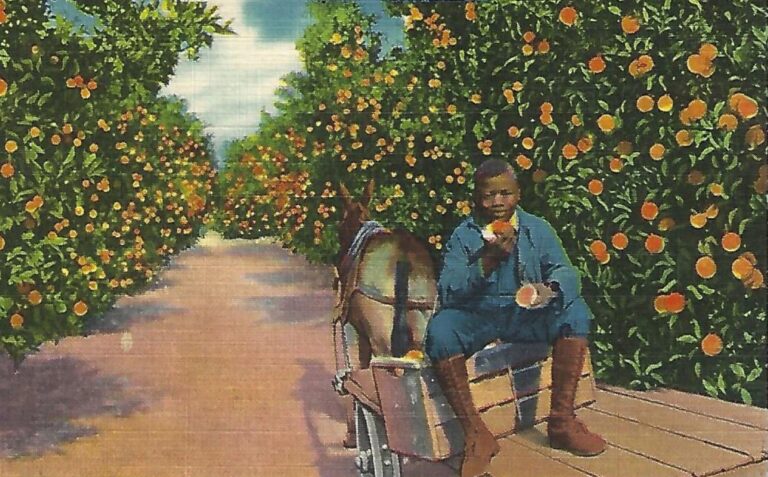

Again, every stablecoin transaction will be monitored and recorded, and a third party (be it a government or private entity) can restrict who can pay for what and when. This can even be done automatically via an algorithm and be based dynamically on other data, such as a social credit score system or other ranking. In other words, two people will not necessarily be able to do the same thing with the same “dollar.” Also, both CBDCs and stablecoins will most likely speed up the phasing out of physical cash, which is what will ultimately complete the absolute and inescapable surveillance state and accomplish complete control over every aspect of human life. Whether a digital currency is issued by the Fed or by other private entities is a technicality that does not change the fact that both digital payment modalities end privacy and enable total control down to the smallest daily transaction.

It is important to note that the owners of the Federal Reserve banks themselves may well issue stablecoins, thus creating a programmable digital currency with all the dangers of a CBDC, without the congressional policy and oversight protections currently existing for the Federal Reserve.

V. Conclusion

The GENIUS Act primarily codifies and regulates stablecoins. It does not create them, but it defines them and thereby provides both legal certainty and legitimacy. This is likely to substantially increase the popularity and adoption of stablecoins. As a result, there is likely going to be an increased demand for U.S. Treasuries, which will help the federal government finance the national debt but may also reduce the amount of capital available for economic growth (e.g., through stocks and loans).

Ultimately even more impactful, however, will be the effect of mass adoption of stablecoins on individual liberty and human freedom, especially if stablecoins increasingly replace cash.

Programmable money is the key requirement for total control of human behavior. An all-digital payment system will allow for global tyranny and leave no way for a human being to try to escape into freedom. Whether this payment system is run by a central bank, a government, or private entities makes little difference. By design, stablecoins, like CBDCs, not only allow for the complete and permanent documentation of every single transaction, however insignificant, but make it possible to allow or deny individual transactions remotely and automatically, down to the smallest detail. Hence, for example, you might be able to use a stablecoin to purchase a snack but not a train ticket, if some decision-maker or algorithm so decides.

This is exactly how the Chinese system works. Although the GENIUS Act does not implement a social credit score system, stablecoins (which the Act codifies) allow for the easy activation of one. During the next lockdown, it will be easy to deactivate “nonessential” businesses’ ability to receive payments. Likewise, it will be easy to disable “nonessential” individuals’ ability to make payments (or to tailor closely where and on what they may spend their stablecoins). Unfortunately, the very same mechanisms that are intended to combat crime, terrorism, and money laundering can also be used to penalize people protesting against their government, refusing to participate in medical experiments, or holding the “wrong” political views.

It is important to remember that stablecoins offer neither privacy nor an alternative to the dollar (or other national currencies, for that matter). Hence, they are fundamentally different than what cryptocurrencies seemed to (accurately or falsely) promise. In the most important aspects, they are instead like CBDCs with a different issuer.

Thankfully, the GENIUS Act does not abolish cash. It also does not abolish traditional forms of banking. However, it codifies a serious competitor to both. It is ultimately up to each individual to decide whether to use this new road to enslavement, marketed as “convenient,” or to reject it. Most likely, there will be increasing corporate pressure to use stablecoins for various transactions, but most businesses want to sell and are, therefore, limited in the extent to which they can force unpopular measures on their customers, as long as the customer has an alternative, such as taking their business to a competitor. Thus, the consumer actually holds power.

Every single one of us needs to be aware that every single time we pay for anything, we vote: either for freedom and privacy or for surveillance and total control. And whether future generations will understand what liberty means will depend on how we vote today.

Endnotes

- https://www.congress.gov/119/bills/s1582/BILLS-119s1582enr.pdf

- Office of Public Affairs. Five Major Banks Agree to Parent-Level Guilty Pleas. U.S. Department of Justice, May 20, 2015. https://www.justice.gov/archives/opa/pr/five-major-banks-agree-parent-level-guilty-pleas