As U.S. taxpayers get squeezed by heavy price inflation, escalating property taxes, and the rising cost of homeowners and car insurance, some are beginning to realize something that comes as an equal slap in the face: their tax dollars and insurance payments are financing an invasive digital prison.

Specifically, municipalities—from rural counties to larger cities—are falling for the sales pitch that they need to dedicate scarce local tax dollars to “keep up with the Jones” by installing invasive high-tech surveillance systems in their communities. In many instances, officials are quietly putting these systems in place without public disclosure or debate. (Some are also circumventing normal budgetary processes and transparency by engineering public-private partnerships, obtaining state or grant funding, or using funds obtained through asset seizure and forfeiture.)

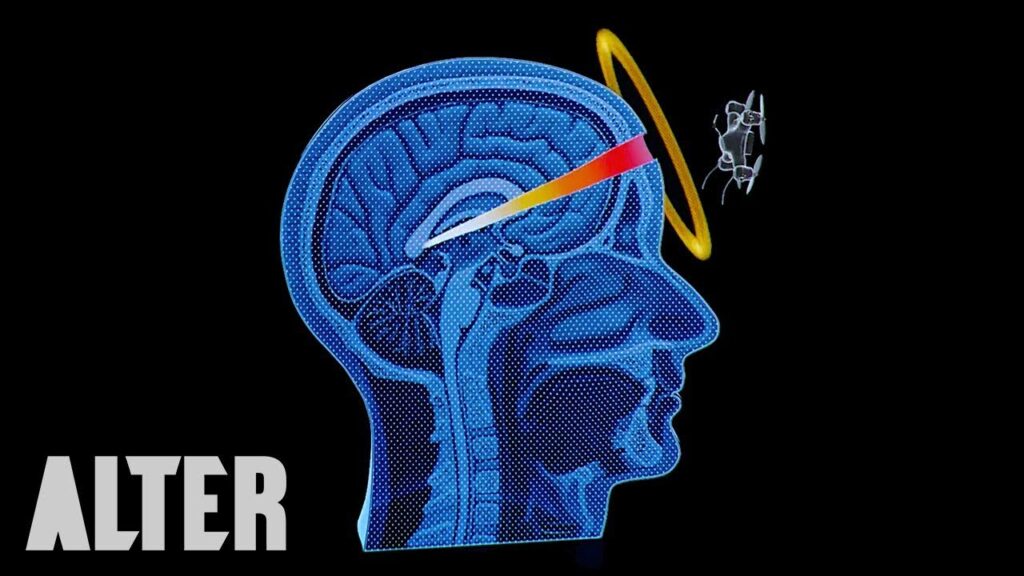

Among the technologies that have received recent attention are license plate readers (LPRs). The cover stories for their deployment are “crime prevention” and “public safety,” but as technology watcher Naomi Brockwell summarizes, the “smart” cameras and video analytics actually create “a cloud-based surveillance network logging your movements in real time, and creating a warrantless database for law enforcement.”

One of the top contractors providing LPR and related technologies is Flock Safety, which is up-front about the intentions of its governmental and other clients: to use Flock’s “end-to-end suite of hardware and software” to connect “cities, law enforcement agencies, businesses, schools, and neighborhoods” into a nationwide network. (Other contractors providing similar services include Leonardo, Brite, Motorola, and more.) As Flock Safety also explains, “In spite of the way the [LPR] technology is named, the automated license plate reader does not actually need a license plate to identify a vehicle”:

“The company says the AI-powered tool captures a vehicle’s ‘fingerprint’—attributes like make, model and color as well as other features like decals or bumper stickers, roof racks and even temporary paper plates. All these can be used to find a vehicle in the data.”

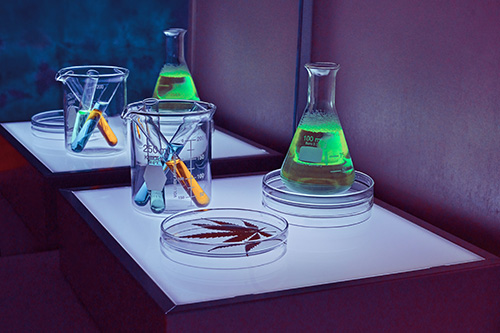

LPR surveillance would be bad enough, but the interoperability of LPR databases with other sources of data—such as Ring cameras, drone surveillance, and the data centers that power AI—makes the situation even worse, creating a true Big Brother “panopticon.”

Fortunately, the realization is hitting that we can push back against financing our own surveillance. Activists and local politicians around the country have successfully worked to end their municipalities’ contracts with LPR companies like Flock and remove the cameras. As cities that have ended water fluoridation have discovered, canceling local government expenditures—whether on poisoning or surveillance—liberates tax dollars for far more constructive purposes.

We encourage you to use the resources assembled here, first, to become informed, and then, to take action.