Become a member: Subscribe

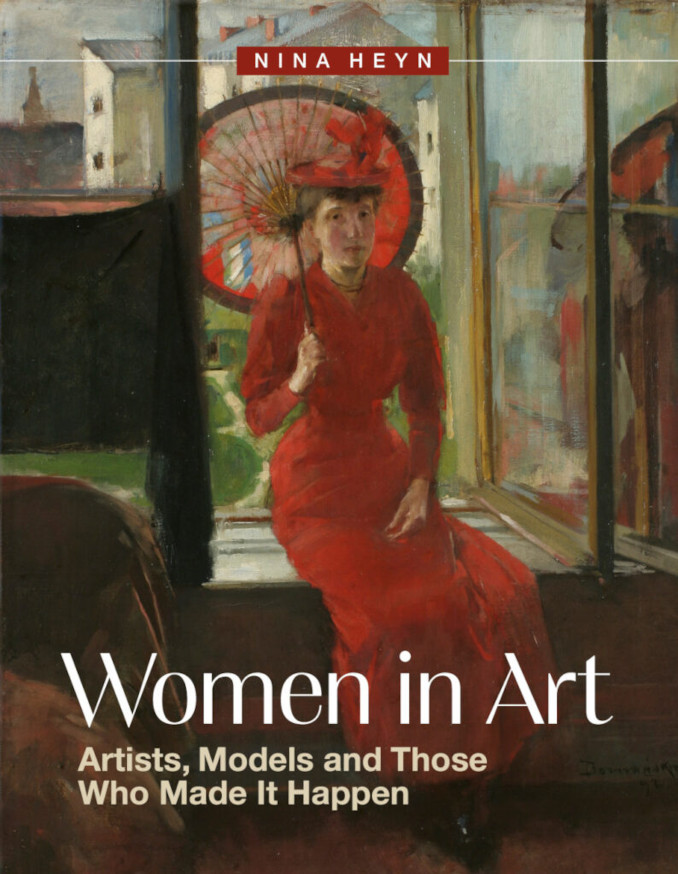

Food for the Soul: Women Who Made It Happen – The Last of the Medicis

By Nina Heyn – Your Culture Scout

Anybody who has read anything about the Renaissance is familiar with the name of the Medici banker family. There are many stories about Cosimo the Elder and Lorenzo the Magnificent—men who were patrons of Botticelli, Vasari, Bronzino, Michelangelo, and Raphael. Much less is known or remembered about the last of the Medici family…and the one who turned out to have the most significance for the generations who came long after the Medici dynasty was no more.

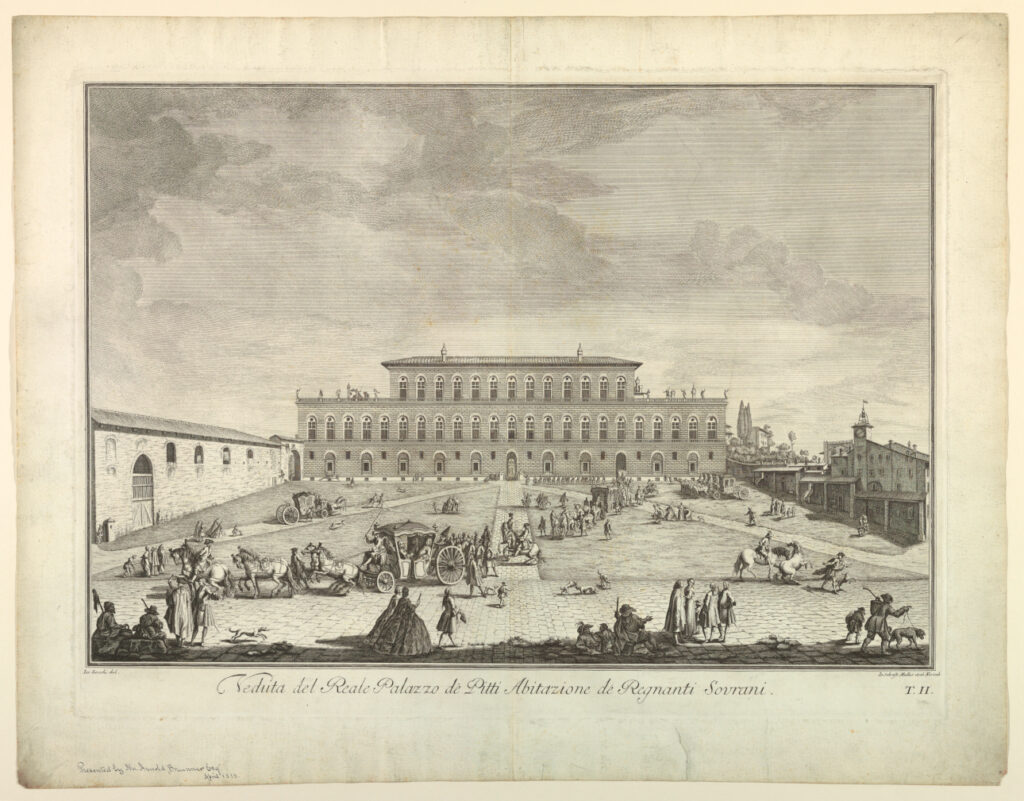

The 18th-century descendant of the great Renaissance Medici rulers, Cosimo III de’ Medici, lived to age 81, but his reign was marred by an inability to secure the continuation of the family line. He had two sons, but neither of them produced any children. Therefore, Cosimo III arranged in 1714 to pass the succession rights to rule the Florentine Duchy to his daughter Anna Maria Luisa (normally, the succession would travel though the male line of descendants). Four years later, the European superpowers of England, the Netherlands, France, and Austria signed a secret treaty to torpedo those succession plans, agreeing between themselves that upon the death of Cosimo III (or his childless son Gian Gastone) the Tuscan lands would pass to Charles of Bourbon. When Cosimo III learned of this secret pact to divide the Medici inheritance, he was outraged. He reinforced his army and publicized Anna Maria Luisa’s succession plans to gain popular support. Upon his passing, his son Gian Gastone proved to be a poor ruler, but he did confirm Anna Maria Luisa’s rights to inherit the Medici family estate, which included L’Uffizi, Palazzo Pitti, and various Medici villas outside Florence. Eventually in 1737, Gian Gastone succumbed to his numerous illnesses and alcoholism, leaving his seventy-year-old sister as his sole heir.

At this point, Anna Maria Luisa de’ Medici (1667-1743) had already survived her husband, the German Elector Johann Wilhelm II, and she would survive her brother for another six years. As the last of the illustrious Medici family whose history was intertwined for so long with the lives of the Tuscan people, the princess decided to give back to those people a truly princely gift.

Anna Maria Luisa willed the entire Medici family estate, including the art legacy contained in the Uffizi Gallery, Palazzo Pitti, and other Medici homes, to the Lorraine dynasty but for the exclusive use by the people of Florence. Her will expressed it this way: “The Most Serene Electress cedes, bestows and transfers…galleries, paintings, statues, libraries, jewelry and other precious things…upon the express condition it be maintained as ornamentation of the State, for public use and to attract the curiosity of foreigners, nor shall it ever be removed or transported outside of the capital and the Grand Ducal State.”

In this way, not only did the princess make the trove of Italian art the permanent property of Florentine citizens, but with foresight, she also ensured that this profusion of unique art would serve as an attraction to income-producing visitors. With the stroke of a pen, she provided the Tuscan people with a repository of treasures that would remain economically advantageous in perpetuity.

The 18th and 19th centuries were the age of so-called Grand Tours—long trips undertaken by the aristocracy as well as artists and writers, who traveled to Italy and Greece from their home countries (most often England and France) to “take in culture” and polish the classical education that all well-born men (and a very few women) would have received at universities. Part of such a Grand Tour trip would have been stops at the main Italian cities: Rome (for antiquities), Venice (for the carnival), and Florence (for Renaissance and Baroque art).

The picture above could serve as an illustration of such a Grand Tour moment, showing English aristocrats visiting the Uffizi to admire the Medici trove of art. The Tribuna of the Uffizi was painted by Johann Zoffany, who specialized in making portraits of English aristocrats, as well as creating group portraits. This painting was a commission for Queen Charlotte (wife of King George III, the Hanoverian dynasty ruler of England in the 18th century), and it belongs to the genre of “conversation pieces”—informal portraits of groups of people. A master of this genre, Zoffany was tasked with creating a group portrait of English courtiers, gathered in the octagonal room of the Uffizi, surrounded by the most famous artworks in Florence. Most of the sculptures and paintings in this picture are identifiable pieces from the Medici collection, now housed either at the Uffizi or at the Palazzo Pitti. Unfortunately, Zoffany placed Titian’s Venus of Urbino at the very front of his painting, and this bold Renaissance nude, shown so prominently in the 18th-century picture, together with some inside jokes showing titled visitors admiring buttocks and breasts of sculptures, was too much for the royal patroness. The endeavor broke Zoffany’s relationship with Queen Charlotte, forcing him to find new clients on new shores; he traveled all the way to India, where he spent years painting local VIPs.

Had Anna Maria Luisa not stipulated in her will that the entire Medici collection was to remain the unsellable, inseparable property of the city of Florence, it is likely that the most unique and precious art of Renaissance Italy would have ended up in the hands of British collectors in the 19th century and American dealers in the 20th century. Florence is no longer a center of the cloth trade, as it was in the Middle Ages, nor is it the banking power that it was in the Renaissance, nor is it a seat of regional political power, as it was in the Baroque. None of the things that were so important to the men who ruled Tuscany—whether the Medici or the Lorraine-Savoy dynasties—lasted into our times. What remains to this day, continuing to ensure Florence’s wealth and importance, is the art, largely preserved by this princely will. The princess used her position and foresight to create a gift of art that has kept on giving for centuries.