Become a member: Subscribe

Book Review

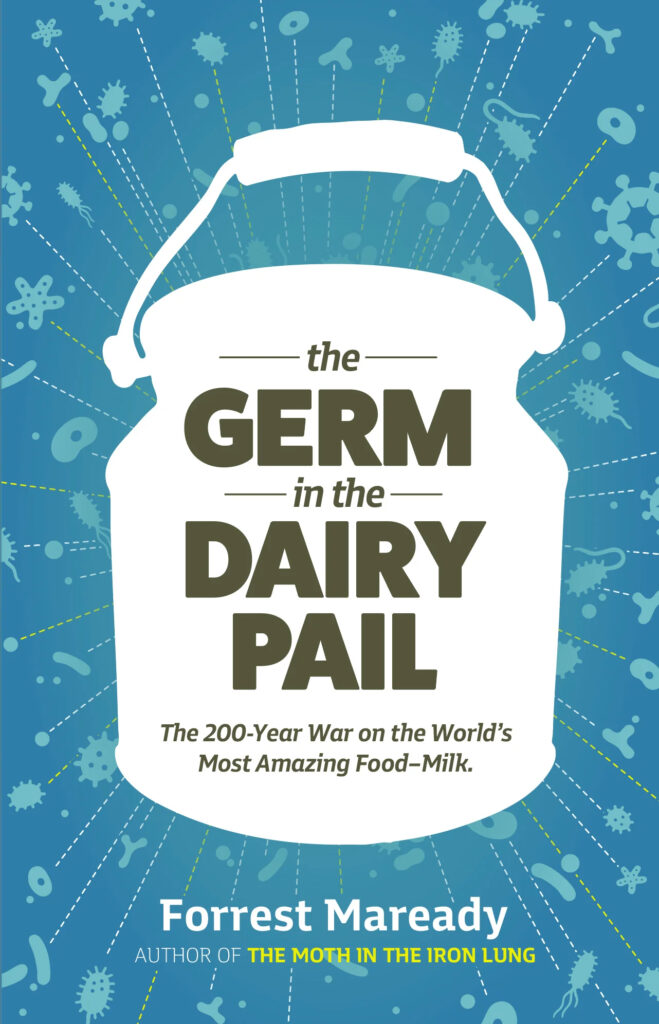

The Germ in the Dairy Pail

The 200-Year War on the World’s Most Amazing Food—Milk

By Forrest Maready

“Life in all its fullness is Mother Nature obeyed.”

~ Dr. Weston A. Price

The Germ in the Dairy Pail

The 200-Year War on the World’s Most Amazing Food—Milk

By By Forrest Maready

Book Review, January 13, 2026

By Pete Kennedy, Esq.

The Germ in the Dairy Pail is a fascinating historical narrative about what author Forrest Maready describes in the subtitle as “The 200-Year War on the World’s Most Amazing Food—Milk.” The book asks and answers a simple question: How did a food that sustained civilizations for millennia come to be considered as decidedly unhealthy? He captures perfectly the pattern that emerged with milk (as it has with many other public health matters):

“[A] public health threat emerges often legitimate. Authorities respond with broad regulatory measures addressing a symptom rather than a cause. Those measures calcify into dogma and eventually, the original concerns transform into absolutist positions disconnected from any emerging evidence that might point to the cause.”

The biggest public health threat, Maready observes, is fear itself.

Before the war against nature’s perfect food started, raw milk had sustained civilization for thousands of years, both as a food and a medicine. The book states, “historical records from Boston indicate that certain dairies commanded premium prices for ‘medicinal milk’ prescribed by physicians.” Maready notes that milk from clover-fed cows was prescribed for respiratory conditions, while milk from cows fed on timothy grass was believed beneficial for digestive complaints. He quotes a Dr. Benjamin Smith Barton, who said, “Milk contains within it the very essence of the plants consumed by the animal, transferring their medicinal properties in a form more easily instituted by the human constitution.”

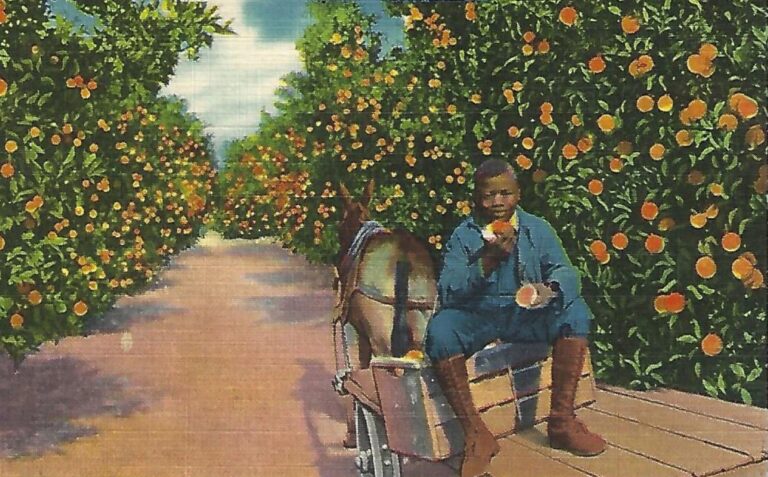

The conditions leading to the start of the war on raw milk began during the War of 1812, when the British naval blockade of American ports led to severely reduced access to Caribbean-imported rum—the country’s alcohol of choice. The blockade also affected the export market for America’s grain farmers. The upshot of the two developments was a transition from rum to whiskey as America’s most popular alcoholic beverage. New distilleries started up, many in urban areas. American grain farmers now had a new domestic market to replace their lost export business.

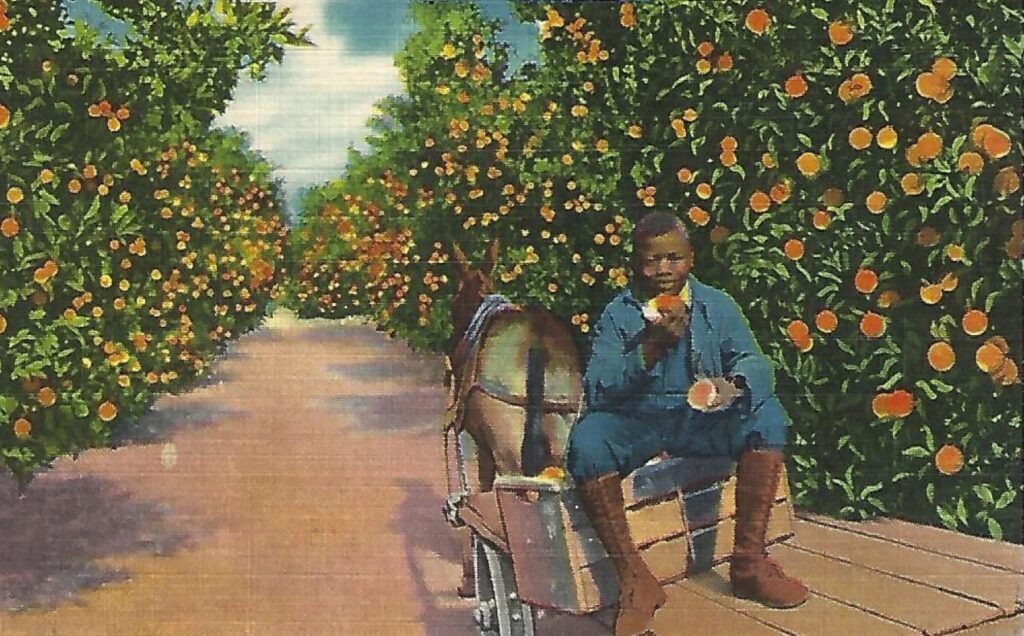

During this same period, urbanization was growing at a rapid rate, with greater numbers of Americans living separate from the sources of their food. More dairies settled in the cities, where they used distillery waste from the whiskey manufacturing process as a chief source of feed for cows; this enabled the distilleries to dispose of their spent grain at no cost or even a profit. Urban dairies—consisting of diseased cows in cramped quarters consuming distillery waste—led to the production of swill milk, a blue-colored substance responsible for the deaths of thousands of infants during the 19th and early 20th centuries. Maready states, “The milk that reached consumers was frequently diluted with water to increase profits, then adulterated with chalk to restore its white appearance, molasses to improve its taste, and various chemicals to prevent visible spoilage. Without the adulteration, the color of the milk was blue.”

The decline in raw milk quality in the cities led both rich and poor to turn to “patent foods” and artificial infant formula instead; in the cities, the number of mothers breastfeeding declined. The patent foods and infant formula were nutritionally deficient, further contributing to disease.

Dairies in the countryside using traditional practices continued to produce quality raw milk but, as Maready says, “The stage was set for a fundamental shift in humanity’s relationship with milk. No longer viewed as a natural product that simply spoiled over time, milk became understood as a dangerous biological fluid, requiring technical intervention to render it conveniently safe.” Instead of working with nature, man was now trying to control it.

Although journalist Frank Leslie exposed the unsanitary conditions in urban dairies as early as the 1850s, that attention did little to slow down the swill milk trade. Thousands of infants, children and adults continued to die from diarrhea and other diseases caused by the consumption of raw milk. The urban confinement dairies, along with the transport of diseased livestock across the country, led to the onset of bovine tuberculosis, a disease transmitted to humans. The long-distance transport of unrefrigerated milk in trains further contributed to the public health problem of adulterated milk.

Clearly, the problem wasn’t milk itself but rather its production practices. However, instead of going to the root of the problem and getting rid of the urban dairies and their unconscionable practices, the dairy business changed from producing a living food—with an emphasis on terrain and cows feeding on fresh grass—to a mass-produced commodity that perpetuated underlying nutritional problems. Pasteurization—the technology introduced to address milk quality and safety—was not designed, as Maready observes, “to preserve milk’s natural qualities but rather to mask its deficiencies.”

Chicago’s Municipal Milk Ordinance of 1873 was one of the first laws to mandate pasteurization. The steam pasteurization required to be in compliance with the Chicago law was cost-prohibitive for some of the smaller dairies, forcing them out of business. As one physician noted at the time, “health regulations mistakenly conflate pure, farm-produced milk with contaminated swill milk, unjustly burdening rural producers.” Pasteurization turned milk into a commodity—standardized, uniform, industrial, and marketable—where the emphasis was on quantity, not quality.

Even as the country moved toward the industrialization of the milk supply, some physicians were using raw milk as a remedy to treat chronic disease:

- Dr. J.R. Crewe “documented hundreds of cases in which patients with chronic digestive ailments improved dramatically when switched to an exclusive raw milk diet.”

- Dr. Charles Sanford Porter, in charge of a Florida sanitarium, wrote in a 1905 medical journal, “I have witnessed the complete recovery of patients suffering from chronic dyspepsia, colitis, and even tuberculosis through exclusive raw milk diets.”

- A strict raw milk regimen, physician-directed, cured John D. Rockefeller’s dyspepsia; Rockefeller drank nothing but raw milk for two months, drinking up to nearly one gallon a day.

- Sanitariums in Battle Creek, Michigan, and Danville, New York, offered exclusive raw milk regimens for digestive disorders.

- Upton Sinclair claimed a raw milk diet improved his energy, mental clarity and digestion; he publicly reported on his health recovery, emphasizing milk’s nutritional completeness and the importance of consuming it raw.

Doctors prescribing the raw milk cure even encouraged patients to relocate temporarily to access the highest quality supply of raw milk. Some doctors tried to establish an alternative to pasteurization with the formation of the Medical Milk Commission (MMC), an organization dedicated to the production of safe raw milk through rigorous inspection, testing, and standards. Dr. Henry Coit, the MMC’s first president said, “The certification of milk by medical milk commissions offers the best solution to our milk problem. Not through heat which destroys vital elements but through cleanliness and careful monitoring.” Coit said that pasteurizing milk was trading infectious disease for malnutrition. Unfortunately, the MMC certified just 17 dairies.

While Coit was championing carefully produced raw milk, businessman and Macy’s co-owner Nathan Straus was winning the day with his campaign for mandatory pasteurization. Pasteurization had lowered the incidence of disease in the areas where swill milk was sold, so government officials increasingly sided with Straus and his contention that pasteurization was the only way to ensure milk safety. There could have been a regulatory system allowing raw and pasteurized milk sales to coexist on a more equal legal footing, but as Maready points out, regulators had trouble with “the notion that bacteria could be both harmful and beneficial,” instead holding “an oversimplified view that overlooked milk’s remarkable biological complexity.” Milk “wasn’t a sterile liquid contaminated by invaders but a dynamic ecosystem with its own balance and relationships.” The war against harmful germs thus led to the unwitting elimination of beneficial ones that had been with humans throughout time.

Ironically, as government regulations were moving closer to mandatory pasteurization, scientists were learning more about the benefits of raw milk and its nutrients, including, for example, the “mysterious life giving substances [vitamins A and D] partially destroyed by heating.” The fortified vitamins A and D added to milk after pasteurization are poor substitutes for the originals. Maready also observes, “Milk isn’t simply one substance; it’s hundreds of different bioactive molecules working in concert. Proteins, fats, and carbohydrates are just the beginning of its complexity.” The likelihood is that science still hasn’t discovered all the beneficial properties of raw milk. When scientists do discover new benefits of raw milk, the regulatory agencies seem determined to double down in making access more difficult. Consumers often haven’t helped themselves by deferring to authority instead of using their own senses.

In 1906, the federal Food and Drug Act cemented pasteurized milk’s dominance over our food system. The newly formed Food and Drug Administration (FDA) was fully on board with germ theory and the belief that the only good bacteria are dead bacteria. No government agency has been more hostile to raw milk sales than FDA. As Maready says, “Milk sits at the intersection of one of our most contentious public debates—do our government officials have the right to choose what we may eat or drink?” FDA’s answer would be in the affirmative; in response to a 2010 lawsuit to overturn the interstate ban on raw milk sales, FDA stated in a court document that there is no fundamental right to feed either yourself or your children the food of your choice.

Around the time Congress created the FDA, Maready observes, battle lines were drawn between “public health officials, urban physicians, and industrial dairy operations versus milk diet practitioners, traditional farmers and consumers who preferred raw milk’s taste and digestibility.” The 1910 publication of the Flexner Report helped ensure the rise of pharma, the increased federalization of milk regulations, and the winning out of fear and a mechanistic view of life. In 1924, FDA published the Pasteurized Milk Ordinance (PMO), a document governing the production and distribution of raw milk for pasteurization; today, all 50 states have adopted the PMO. In 1965, the PMO was amended to require that only pasteurized milk be sold to the final consumer; the great majority of states have not adopted this provision. In 1987, FDA, in response to a court order, issued a regulation banning raw dairy products (other than cheese aged 60 days) in interstate commerce.

Maready mentions several recent enforcement actions taken against raw milk farmers; however, enforcement actions aren’t as common as they were 12 to 15 years ago. The bias of regulatory agencies against raw milk continues, but—in the face of growing demand for the product—there are state agencies now that would rather not regulate the product at all. Arkansas, Iowa, North Dakota, and West Virginia have all passed laws in the past couple years that legalize or expand raw milk sales; all of these call for little or no regulation.

Surprisingly, Maready does not mention Sally Fallon Morell, president and founder of the Weston A. Price Foundation (WAPF), who has done more to promote and foster demand for raw milk than any other individual. When Fallon Morell started the Campaign for Real Milk in 1998, 27 states had legalized sales or distribution of raw milk in some form; today, that number stands at 47. That said, there is still a ways to go in changing the laws to give raw milk the market access it rightly should have.

I highly recommend The Germ in the Dairy Pail for those interested in understanding how the dairy industry, regulatory agencies and public health caused nature’s perfect food to lose its way. The good news is that as demand for raw milk continues to explode and the number of small-scale dairies continues to increase, the country can get back to where it was before the mandatory pasteurization laws took effect—where small farms dotted the countryside, providing a nutritious product for those in their communities.

Buy the book HERE.

Log in or subscribe to the Solari Report to enjoy full access to exclusive articles and features.

Already a subscriber?